Gen Z athletes are rejecting hypermasculinity in sports

In partnership with Roman

Masculinity: let’s talk about it. From the inception of our site back in 2016, our mission statement has been to redefine masculinity. A year and a half later, masculinity is now front and center in our national conversation. It’s why we decided to launch our first Masculinity Week. We’ve partnered with a company that shares our values with Roman, a company that’s redefining the relationship men have with their own health. They believe that the more we talk about, communicate, and confront our problems, the more empowered we’ll be. This week, we’re introducing important stories unpacking masculinity and how we, as men, can empower one another. We’re in this together.

BJ Sanders was an all-star high school football player who had his sights set on Division 1 colleges, maybe even the NFL. His future was bright. He was headed towards his dreams and all seemed to align.

But then he decided to walk away from it all.

“There was a very serious altercation with one of my coaches,” he recalls to Very Good Light. “It was to the point where we almost fought each other.”

SEE ALSO: The one thing everyone misses when they talk about masculinity

The cause? What BJ says is hyper-masculinity, an exaggeration of extreme male stereotypical behavior, one that emphasizes sexuality, aggression, physical strength.

Hyper-masculinity, or often dubbed “toxic masculinity,” has been on the tips of everyone’s tongue as of late. It’s what psychologists and behaviorists say is a cause for self-harm or harm to others and is especially pervasive in sports.

“The amount of ‘pussy,’ ‘pansy,’ soft comments like that from my main trainer, who was getting these colleges to talk to me, and athletes on the team was just very frustrating.”

The ways in which masculinity expects athletes to excel, limits and restricts athletes from experiencing a three-dimensional human experience. They’re conditioned to limit emoting feelings, being vulnerable or expressing a need for help. Our culture unfairly places athletes on pedestals for their strength, but in turn, confines them to being one-dimensional creatures. It not only isolates them but creates real problems – like mental illness.

BJ recalls an incident during his junior year. It’s when he had a groin tear so severe, he couldn’t hinge at the hip and needed surgery. Instead of words of encouragement or sympathy, BJ received judgment.

“The first comment I got when I finally got back to practice a few days later, was, ‘Did your lips tear?’ Pretty much saying that I had a vagina and that my… you know,” he says. “The amount of pussy, pansy, soft comments like that from my main trainer, who was getting these colleges to talk to me, and athletes on the team was just very frustrating. It feeds into this unrealistic mold of this toughness that surrounds successful athletes and the competitive nature of sports right now.”

It’s no wonder why there’s been a microscope placed onto athletes as of late. The pressure has amounted to something so big that men are now starting to speak out. It was in February that NBA All-Star DeMar DeRozan tweeted out a need for help. “This depression get the best of me…” he wrote. Cleveland Cavaliers star Kevin Love wrote a powerful essay about the anxiety he experiences. A few weeks ago, Oakland Athletics star Stephen Piscotty was seen grieving the loss of his mother on the baseball field. He was jeered for showing emotion.

It’s clear that masculinity needs to evolve – and not only in sports. After all, hypermasculinity doesn’t just start and end with athletics. It starts when boys are young. It starts when boys fall down and we tell them, “Man up.” S’top crying.” “Boys don’t cry.” We’re socialized to accept that boys shouldn’t express physical pain, let alone emotional pain, and our prized athletes, especially, should be immune to pain and bulletproof. Masculinity suppresses them and chokes them of being human.

But the good news is this: masculinity is quickly evolving with the future generation of men. We can see this with BJ, who’s speaking out on hyper-masculinity and machismo, becoming allies to others on and off the field.

“[Hypermasculinity] made me quit a sport, honestly,” BJ admits. “It’s such a negative thing for all people, and that’s something that I didn’t want to represent, to become, to conform to.”

Today, BJ plays basketball at Sarah Lawrence College, a place where he feels he can be himself.

He says his new group of teammates are open, honest, and most importantly, vulnerable.

We’re socialized to accept that boys shouldn’t express physical pain.

They talk to each other about everything from bad grades, girl drama, injuries, everything. When a player is in his head during practice, they pull him to the side and give him space to share what’s on his mind. No judgement. This creates pathways for players to become a team and for teams to thrive.

“Speaking from experience, I had a lot of anxiety with games and a lot of different other things,” BJ opens up. “I was able to sit down with the guys, everyone – every single player on the team, the coaches, and all – and open up about a few things and get perspective of what’s going on and how to handle that situation on the court.”

We spoke to several Generation Z athletes from across the country on their own experiences with sports and how they’re changing it for the better. This is what they had to say.

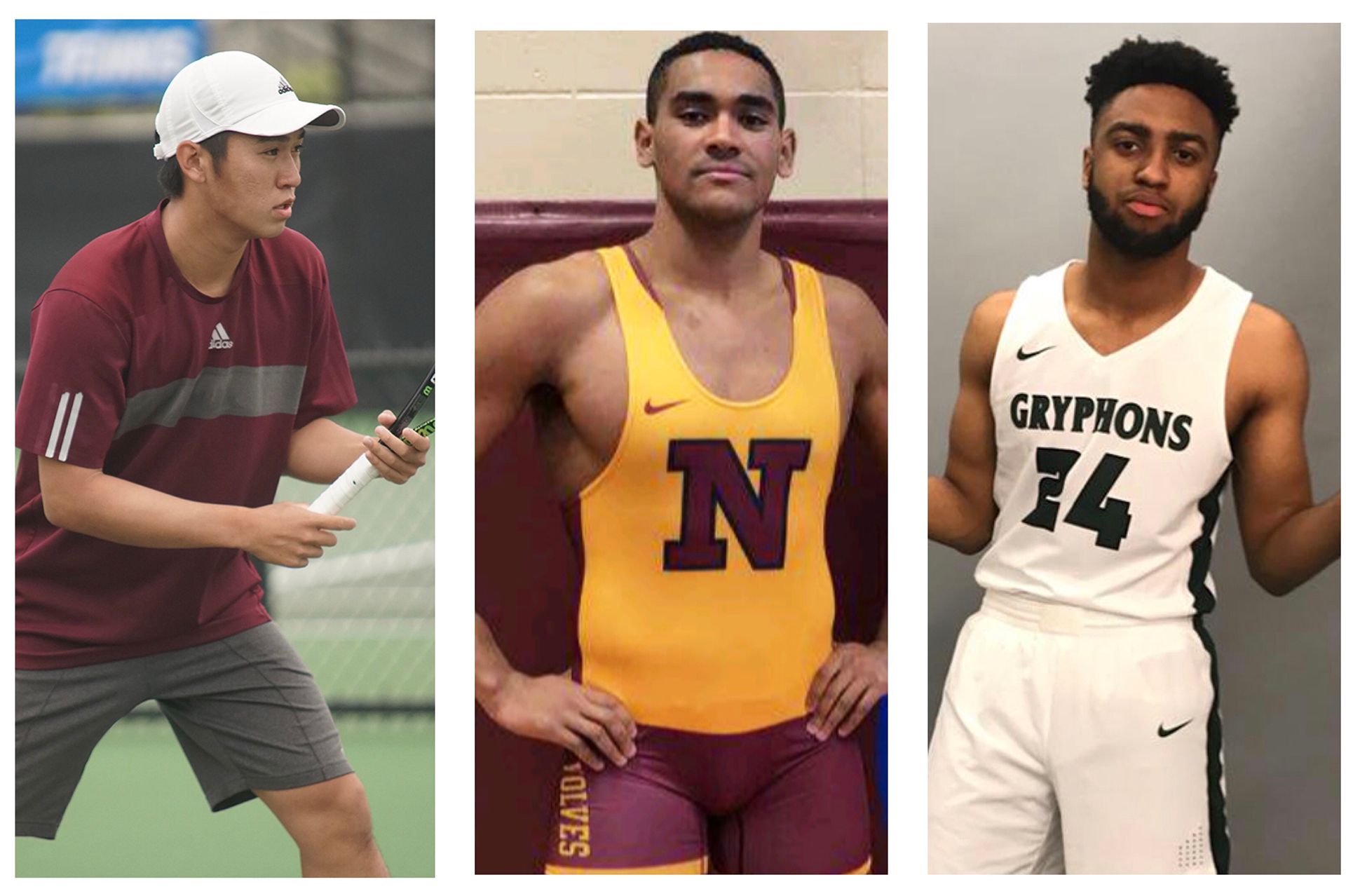

Justice Horn, 20, wrestling, Blue Springs, MO

How do you think society describes masculinity on the field or on the mat?

I think what society describes masculinity on is just years and years and generations of what a typical man should be and act like on the field of play, and then I feel like even off the court and off the mat, you’re supposed to act a certain way. Certain norms would probably be very narrow minded things like a man should be into weight lifting; he should like to drink, to go out to party, and even be a little misogynistic. It’s just stereotypes like that. You have to keep up a façade of being this ideal man.

In playing a very hyper-masculine sports, did you ever feel the pressure to keep up this façade of masculinity?

Yeah, I really did. I think it depends on the generation and the time, but I did really struggle with that my early high school years because I was thinking not to be too feminine and that I needed to be masculine cause I was out at the time. I didn’t want to be in double jeopardy and I did feel like I had to live up to that. But now, I don’t think it matters because our generation is being a lot more open minded and I think, really, where that comes from is having inner confidence that you know who you are.

How would you say that weakness in sports is viewed?

I think in the sports world, things in your personal life are a lot easier to accept, but if you’re weak physically and you’re not performing, it’s a different scenario. What I mean by that is, in the sports world, we really do accept people of any creed, but if you’re not performing, people don’t like that. But then, mentally, you always kind of have to put up a façade of being strong, being a leader, being dedicated to something, being dedicated to a that sport you love. It is a weakness and it isn’t a good thing. Even in the NCAA, they’re doing a good job about being fine with sharing your weaknesses, not only physical. For example, my concussion [when I played] football was really shunned on, like it was a secret. That’s one instance on the physical side. And then on the other side, on the mental side, the NCAA has been doing a good job with how we think about mental health. It’s good because athletes and students can share that and it’s not seen as weakness. You can get help and it’s not so taboo as it really was back even five or ten years.

You guys have been having more opportunities to open up to each other and you guys have been and you guys are all more supportive of each other. What are some examples and way coaches and teammates are being more supportive of each other?

Nothing is off subject and anything can be talked about. I think that really creates an open atmosphere because everything is so open and nothing is frowned upon. I think it’s just having an open environment and just knowing that not only is it an open environment but that it will be met with love and support and I think that’s what creates such a good team atmosphere and such an open, accepting atmosphere.

Between society at large and the sports world, there is a disconnect about how athletes can have emotions. Do you have any thoughts about that?

I totally agree with that because just being an athlete, you’re kind of put on a pedestal and you’re seen as, especially in the big leagues, perfect. You can’t have problems and you almost can’t not have a perfect life. But I think that’s a misconception because although we might look like gods on the field of play, we’re regular people and a lot of people need to understand that. We may deal with anxiety or have physical problems or even mental health problems. There is a disconnect because we see athletes as champions as if they’re immortal.

Jeremy Yuan, 18, tennis, Johns Creek, GA

How do you think people define masculinity and how do you define masculinity?

I guess masculinity is like a social pressure from peers and media to look a certain way, perform a certain way, and behave a certain way. Personally, I haven’t had a lot of pressure when I play because of my surroundings and circumstances, but I can imagine for more stereotypically masculine sports, where you’re expected to look more masculine and behave more masculine, it could become an issue.

Tennis isn’t a conventionally masculine sport, but do you still feel the pressure to be masculine because you are an athlete?

Yes, especially in college, where everybody is working out and getting a lot bigger and stronger than they were in juniors. It’s important to be physically intimidating, which can benefit you, but the benefits are smaller than in other sports. There’s less of a need to be physically bearing than in something like football.

Do you think that as an athlete, that societal pressure to be masculine affects you?

Personally, I think I’m doing okay. It’s a lot easier to get by without satisfying the masculinity in tennis. There’s a lot of non-perfectly-masculine people who do really well in tennis. I think that would be a much bigger issue in other sports, but in tennis, it’s definitely on the lower side. You’re definitely able to succeed and there is less social pressure to be masculine in tennis than in other sports.

What do you think would happen if you or somebody on the team were really struggling with something that could bring the team down? Would you guys share it?

For us, specifically, we definitely would tell and we’d pitch in whenever we could. For example, some people in weird majors have weird schedules and they can’t make practices because their classes run in the afternoon. That’s obviously a problem. One guy told us that he couldn’t make practice this quarter because he had two labs which ran during practice time so he couldn’t make any practices that quarter. That was not good and he needed to keep playing to get better so we thought of a plan. We had a couple of seniors who weren’t in any classes Spring Quarter, so they would play with him in the morning and they would practice again in the afternoon. Different people, whenever they could, were like, “Hey, I got two hours do you want to play a little bit?” Basically we got him as much practice as we could as a team through individual efforts.

BJ Sanders, 19, basketball, Silver Spring, MD

In general, does this hyper-masculinity affect guys in the same way that it affected you?

Yeah, for a lot of people. Look at the NFL and the amount of people who are going through this post-NFL nightmare. For the past 40 or 50 years, NFL players have been using, essentially, foam helmets. Only up until recently did they start revolutionizing the helmets, and nowadays, there are helmets out there that can withstand all but car accidents. It’s so advanced now, but for this 40 year period, heavy hitting athletes were only wearing little foam helmets and getting concussions. Because of this, post-NFL players are dealing with CTE, [a degenerative brain disease occurring mostly likely from repeated head trauma], and there are hall-of-famers, who have had great careers, who are going through extreme anxiety and committing suicide.

We call if having a ringer when you get hit so hard your ears ring, and it’s probably a concussion, but that means you’re playing good. And I went through that. I had three or four concussions throughout my whole football run. Had to go to the doctor’s several times. Had to stay home from school because I couldn’t see anything light. There are NFL players that are even tougher, even stronger, even bigger that do 15 years of this horrible, horrible trauma, and because they have to be masculine and strong, they have to push through that. That’s a brave thing to do, but at what cost at the end of the day? It’s been really rough for a lot of these guys.

How do people expect you to be because you are a male athlete and how are you in real life?

The amount of “You’re nicer than I thought,” “You’re less aggressive than I thought,” “You’re smarter than I thought,” comments I got my freshman year is just disgusting, honestly. That’s a frustrating thing to go through. People expect dumbness, close-mindedness, anger, aggression, and so on both on and off the court. If you come to a game, I do play aggressively because that’s when I play my best, and I try to play my best. But that mind set doesn’t really carry off the court. The expectation, coming from the stereotype of hyper-masculinity, is that we play basketball and we go back to our house and play beer pong and chest bump and do dumb Jackass things, but we’re actually pretty smart guys. People on the team are doing engineering programs and internships in the off season. We don’t follow this mold, and we don’t have to.

What are the type of things you and your teammates open up to each other about and the type of things you guys are supportive about?

You would be surprised. We’re very open about a lot of different things. There’s always been a stereotype that athletes have a tough mentality, and you know, we carry that in practice and games to make ourselves stronger and better for the opponents that are relentless and we have to go up against. But on the court, off the court, if we knock each other over, we help each other up. We talk about injuries, we talk about stress of the day, we talk about feelings, emotions, everything. We make sure our dynamic’s good. If we come into practice and someone’s distracted for something, we sit down, we pull them to the side, “What’s going on?” I think our ability to communicate creates such a strong bond with us.

Speaking from experience, I had a lot of anxiety with games and a lot of different other things, and I was able to sit down with the guys – every single player on the team, the coaches, and all – and open up about a few things and get perspective of what’s going on and how to handle that situation on the court. There’s times where I have checked out during practices and coaches have talked me through and all that kind of stuff. The same with some of our other athletes who are going through something. They get frustrated, angry. It’s so easy to get into a little box by yourself but I think the guys, the coaches, everybody does a good job of communicating how to get ourselves out of these boxes and keep the season going.

You run a sports camp for kids in the summer. How do you coach them?

Because I look at the sport and how it is – and it’s survival of the fittest – I try to toughened kids up. I’ve seen kids that are injured, I’ve seen kids that are crying during the game because they’re nervous to speak up about how they’re frustrated, they’re nervous, or something like that. I’ll pull the kids to the side, stop the game, and all that kind of stuff, because I think that the kids’ psyche and not traumatizing them with that toughness mentality is key to making the kids fall in love with the game and the sport and have fun, cause you know, that’s the biggest thing.

I even do it with my niece because it’s a tough world out there. If she’s playing with kids and she gets hit on the shoulder, I don’t want her crying about it. I tell her, “Pick yourself up. You’re stronger than that,” and it’s the same with the kids on the court. My goal is to foster toughness but in a positive way, not toughness by saying, “C’mon get up you little pussy,” or, “Pansy, get up.” It’s more like, “You’re better than this,” “You can do this!” “Get up, you’re stronger, c’mon,” and if they’re actually hurt or they actually can’t do it, that’s when you give them the empathy to push through. For us to break that mold, it takes continuous patience and toughness.

Andrew Kim, 21, soccer, Aurora, CO

As an athlete, do you ever feel pressure to be a certain kind of guy?

Yeah, I think since you’re with a bunch of other guys in team sports, there’s more chance of conformity. You just have to fit in by acting a certain way. I think that’s what happens when you first join a team. Whether it’s acting like a jock or someone who is a typical athlete athlete. With my overall toughness and whether I got hurt or not and just going through it, I didn’t want to show any weakness towards my friends. Those are the pressures I’ve felt.

Why didn’t you want to show any weaknesses?

I wanted to show that I was important to the team. I wanted to show everyone that I was qualified to be a part of the team like everybody else since it was my first time playing soccer. I wanted to show everybody that I had potential, so no one would, you know, sleep on me.

So it’s important to support your team, but have you ever felt supported by your team when you were insecure about something?

Definitely. I have great teammates who would stay after practice with me and teach me a couple of things or go through games and just look at videos and clips of what I could do better or what they could be better at, so I could learn from their game too. I had pretty good support from my friends and teammates.

Did you have to reach out to them about that?

I definitely had to reach out and step out of my comfort zone. I knew that I wasn’t as good as them but I wanted to strive to be as good as them, so I had to step out and go out of my way to ask. I wanted to be a part of the game, so I knew that if I wanted to be a part of this, I had to step up on my end and on my terms. I had to show to the team that I was working hard. They saw me grow and improve as a player and for them to acknowledge that really made me happy and made me proud of myself.

Yitzhak Franco, 22, dancer, New York, NY

As a dancer, which is seen as feminine in America, do you ever feel like you have to be a certain type of guy?

There’s no way to ignore that thought because, like you said, outside the dance world, it is seen as a more feminine career, but not really. I guess when I was younger, I felt, I don’t know if it was pressure, but the thought of having to be a certain type of guy even within dance and outside of dance and to measure up to these masculine standards was always there.

What made you realize you didn’t have to live up to these standards of masculinity?

I don’t think there was a defining moment, but also, one of the more selfish aspects of dance is that you are working out everyday so you end up having a pretty nice physique. So even going through puberty, all my non-dancer guy friends worried about how buff or defined their muscles were. Whereas, with my dancer guy friends, we’d just be like, you know, regular, because that was our exercise routine. That aspect made me more comfortable and confident in my body and how it presented to the outside world. That was definitely when I would say things shifted.

Between you and other guy dancers, is there a space for you guys to be supportive of each other?

When I was seriously dancing in high school, those were the guys I hung out with all the time, the people I saw all the time. You know, we collaborated a lot – quite physically too, and that creates more space for deeper connections. So there definitely was a space for male dancers.

In high school, I had two really good guy friends, and we’d finish class, go get changed, go to the locker room, and then we’d usually be the last people to leave all the time because we just lagged around and talked. That’s when we would do most of our critical talking about the class. That was usually the conversation starters – what went on that day, who looked really good that day and who didn’t, what we did wrong, and etc. And the consistency in which we would do that, which was most days of the week, definitely allowed me to open up. It could be things from doing really bad to a test, people you had feelings for, and just helping and being close friends.

Do you think that being able to be open with your fellow male dancers helped you guys to be better dancers?

I would say yes because there was an unspoken acknowledgment of the person in the dance studio. You knew them well enough so even if you were just standing in front of them, you were aware that they were behind you. It completely changes the quality of your movement once you’re comfortable being and moving with somebody.

Adam Dalton, 24, runner, Salt Lake City, UT

As an athlete, what forms of masculinity are expected of you?

Track is unique in the way that it’s both a team and individual sport, you’re competing to score points for your team; however, all of the events I competed in were more individually focused. Since I didn’t run any relays, it was always just me out on the track representing my team and racing. I think in that moment on the track, you’re expected to be competitive, aggressive, a team contributor, and those forms of masculinity are always present. But at the same time, you have to stick to the rules of track. You can’t tackle anybody or push anyone to the ground like you can in other sports, otherwise you’d get disqualified. So, it’s more of a focus and competitiveness-based masculine drive that defines masculinity within the realm of track or cross-country, as opposed to a more physical masculinity present within many other sports (i.e. hockey, football, basketball, wrestling, etc.).

As an openly gay athlete, did you ever have to face homophobia from different athletes?

I was out for the majority of my time at Grinnell College, as I came out at during my first semester. At least for me, it was very easy to be myself on my team because at that point, roughly 25% of the men’s XC team identified as queer. Needless to say, there definitely wasn’t any type of stigma present within the team. Generally speaking, most of my competitors didn’t realize I was gay, but once they started to figure it out, not a single person harassed me. It also probably helps that track and cross-country are more niche in terms of spectating; it’s not at all similar to football or basketball where thousands of fans get rowdy and yell all kinds of shit at the players. Because seriously, who goes to cross-country races…basically only significant others, friends, and parents of the athletes; all of whom are generally very supportive and courteous.

Because there were so many queer athletes on the team when you came out, what was the team atmosphere like?

It was really interesting, because the team itself was more queer than other teams undoubtedly. However, when the men’s XC team went from being 25% queer my freshman year down to 2 people my senior year, the culture was almost exactly the same. No matter what percentage of athletes on the team identified as queer, the culture was just kind of the way it was. The Grinnell men’s XC team was always quirky, tight-knit, and supportive. It was also masculine and over-achingly kind of bro-y, but was perceived as less so than other men’s teams on campus. Overall, there’s a lot of team bonding where guys will make fun of each other. It’s not uncommon for guys to say mean things about/make fun of other teammates’ girlfriends, parents, etc. With gay athletes, people would instead make fun of their boyfriends. It was basically equal opportunity teasing. In a weird way, my teammates teasing me in the same way as everybody else was a sign of affection and respect.

Do you think that being friends with everybody on the team and forming your own team family helped you guys to be better runners?

I think so because we all, for the most part, wanted to see each other succeed. We would really push each other to do our best and root for each other. There’s absolutely no money or fan pressure; therefore, everyone does the sport because they love it and more or less appreciate the social aspects the team provides. I think an organic and lighthearted team bond was a great aspect of being a D3 athlete in a more niche sport.

Do you think that this type of closeness between teammates is different from previous generations?

I think the place where camaraderie is coming from and overall the closeness is almost the same, but the way it manifests itself is different. The camaraderie and brotherhood you have between teammates stands regardless of time period; because you have the deep understanding and support of your teammates, and shared connections through sports, your passions, and your goals. That being said, I think people today are more open to talk about tough mental and physical issues. Whereas before, there was more of a you’re a man, you can take this, get through your stuff, don’t let us know about it type of attitude. That, I believe, has changed over time. Also, I think today more male athletes are open to being emotive and thinking for themselves. In previous generations, many coaches were revered as an absolute figure not to question and showing emotion was not seen positively. However, in my experiences, coaching is now a two-way street and athletes have more license to express their emotions.

What is the stigma around being mentally weak, not finishing a race, or not having dedication? How do you as a runner combat that?

I started running because I was in a really small town in Iowa and I went to Catholic school, but I knew I was gay from a really young age. I thought that the way I could become super masculine and not have people think I was gay and be respected was to become a star athlete. I think a lot of my original drive came from wanting to prove myself, so a lot of it was just in my own head. But at the same time, that’s where I originally came from, so my training was obsessive and tough to the point where I ran a race on a broken leg in my senior year of high school because I was that insane to try and qualify for state cross-country. When I got to college and I came out and I no longer had that kind of background, the thing that kept me going was wanting to do my best personally and wanting to be the best I could for my team. That’s where my mindset shifted when I no longer had to prove anything to myself.

My motivation in college was that I wanted to run for my team and I enjoyed what I was doing, but once that was gone, I ran to stay in shape but I didn’t really see the point. But then I ran into a training group in Salt Lake City and I started training with them, and that’s when I regained my love for running and I found that yes, even post-collegiately, you have a family and a team and friends that you can run with. Because of that, I rediscovered my love for running and I started training for a while. And just the self-improvement, the camaraderie, and hanging out with everyone post-collegiately was something that spurred me on and after training for less than a year and being a mediocre D3 runner, I still somehow qualified for the Olympic marathon trials, which still makes no sense to me.

I think that my motivation now is that running is a part of my identity and it’s what I do and I have a good group of people to train with. As long as I’m healthy, it’s something I want to move forward with.

Walter Prince, 21, soccer, Aurora, CO

Do you ever open up to your teammates when you are in your head?

Yeah but only a few of the close ones. It’s easier to be closer to guys in your class cause you’ve just grown up with them throughout the four years. I think everyone has their own way of dealing with it. I don’t really need to talk to anybody about it as much – especially on my team. I think I’m pretty good with dealing with it myself or if I really need guidance, I will call my dad or something. For the most part, I think once you get to this level, you kind of learn to deal with it yourself because we played for a long time so everyone has their techniques to deal with it.

When you do open up to your teammates and your dad, in what ways are they supportive of you?

A lot of it’s affirmation. Just being there to listen to you and hear where you’re coming from. For me, it always helps when someone, even if it’s not practical, gives motivation by saying it’s going to be good, you’re fine, and stuff like that. Little compliments like that are strong and do a lot. Also, when they share their experiences as well, like similar experiences or they’re going through the same thing, it’s a bond, and that helps as well.

In what ways does the bond you guys create when you support each other help you guys to be better athletes?

It makes it a lot more bearable. For example, a fitness session that’s really tough, if you know that your other teammates are doing it with you, it makes it a lot easier. Especially because you guys can talk about it later, like how hard it was, how you guys got through it. That’s how the bond is made, I think. It’s like being able to have a shared experience, and that’s something nobody can take away from you, when you have that shared experience with a teammate and you guys understand the same pain, and stuff like that.

What are the changes you want to see athletes making to step away from insecurities of having to put up a façade?

I would say, for everyone, it’s important to be true to yourself and not really care what society tells you or what you think you should do because whatever identifier you play. For me, something I’ve learned is definitely that concept of being true to yourself and it’s okay to feel the way you feel. It’s not wrong to have feelings and to act upon them. Once you understand that, then you feel a lot more free and you can be more comfortable and that insecurity doesn’t matter as much. I think for athletes now, it’s stepping away from what the definition of what masculinity or toughness used to be. For example, I think it’s tough to say how you feel if you’re sad. If you really follow your feelings, I think that’s pretty tough. I think that’s pretty masculine to be honest cause if you do that, it takes a lot of bravery. But I think that’s not the full definition that people would use now.

As we’re transitioning into a more socially conscious society, we’re understanding that some of these norms created are kind of stupid. I think it’s important for athletes to understand as well that being brave is just as important as being tough. I think that’s the biggest thing. It’s okay to feel how you feel.