“I’m half-Japanese, half-white. I was born in Japan, but raised in the Bay Area.”

That’s how I’ve learned to introduce myself to people who ask where I’m from or what I am. Sure, I could just say that I’m a person, but that wouldn’t be any fun. Without giving away my biological information, how else would anyone place my doe-eyed, ethnically ambiguous, five-foot-six self?

For years, people always wanted to know what, not who, I was. After finding out that I was hapa (that is, half-Asian, half-white), their faces would light up. They’d use words like “lucky,” “cute,” or “unique” to package my racial makeup as something favorable, desirable even.

And for a long time, I believed it, too. I wore my American Seal of Approval with pride, without question. I’m special, I would tell myself. I’m hapa.

SEE ALSO: What it means to be seen as a queer Asian American

That all changed after two specific incidents. The first was when I was discriminated against for not being “white enough.” Specifically, a guy who I’d been exchanging gayzes with all night in the Castro told me that he was only into guys with blonde hair and blue eyes.

I was gagged.

Never before in my life had I been called out for not inhabiting an Aryan physicality, despite being technically 50% Caucasian.

The second –and right on the heels of the first – was my relocation to New York City. One of the initial observations I remember making was how white this city felt. Growing up in the Bay Area, I was surrounded by Chinese restaurants, other families that looked like mine, and friends who also took their shoes off upon entering houses. But in New York City, one of the more diverse cities in the country, I was surrounded by those whose whiteness was never questioned. And with that whiteness came privilege. And power.

In one of the first –and certainly not last –moments of my adult life, I had to seriously face my own identity. This city is famous for that, you know, making you unpack everything you’ve never faced, head-on.

Never before in my life had I been called out for not inhabiting an Aryan physicality, despite being technically 50% Caucasian.

And for me, that was my mixed-race identity. I’d admittedly lived in a bubble for most of my life, leaning into my Japanese identity as my primary identity marker. My whiteness was boring and bland, something that could be colored over with my more interesting yellowness. Rather than seeing this as an opportunity, I left it as something I’d only consider when checking off the “two or more races” box on standardized tests.

But in putting up an Away message to that half of myself, I completely disregarded its gravitas. Because in whiteness, there is a privilege. Not just in this country but globally. And in privilege, there is power and responsibility.

In 2015, 14% – or one-in-seven – U.S. infants younger than 1 were multiracial, according to nonpartisan American fact tank, The Pew Research Center. Compare that to just 5% in 1980. In over 35-years, the population of mixed people nearly tripled. This growth is a direct result of increasing interracial couples and families in America, the proverbial melting pot of the world. By 2060, the U.S. Census Bureau predicts mixed raced Americans will be three times larger than it is now.

But in a country that’s supposed to pride itself on diversity, there still exists a huge race and oppression problem. Black people are being killed at alarming rates, but no one will call this a genocide. The recent election of the President unearthed a collective latent prejudice and xenophobia from white Americans whose ancestors stole this land from Native Americans.

By 2060, the U.S. Census Bureau predicts mixed raced Americans will be three times larger than it is now.

But what does it mean to be mixed race, especially in America in 2018? I have my own ideas of how my two races manifest in different communities, through privilege, and in interpersonal relations. To learn how others, like me, understand and internalize their identity, Very Good Light asked 11 guys of mixed race descent about growing up in America, privilege, belonging, and responsibility. In our first-ever mixed raced campaign, we asked what #mixedracedbeautiful means to them.

This is what they had to say:

James, half-Syrian, half-Italian American

When I was younger, some white family members of mine would make fun of my tan. My legs and feet get especially dark and I remember my cousins would say “Look at these dirty Syrian feet” in a joking way. I completely bottled it up, didn’t think anything of it, because at the time I was very much drinking the Kool-Aid of white culture. Or in middle school especially after 9/11 and learning that I was Arab, people would instantly joke, “terrorist.” They would say, “Well, if anyone is gonna get arrested here, it’s you, James.”

I was this brown spot in a sea of white and I felt like an outcast.

Looking back, I would have simply stood up for myself more. At that young age, it’s so delicate and strange. I would have tried to tell them to not hate a skin tone. Or, I would put them in their place. I’ve removed myself from those certain family members, not because of that one instance, but for many different reasons; they’re missing out. They’re missing out on a whole different perspective on the world. It’s my homework assignment every time I go home and interact with them to make one light bulb go off, one change. It starts at home. It starts with those communities that you grew up in.

I was this brown spot in a sea of white and I felt like an outcast. I couldn’t name a feeling to it when I was younger, but now I know I felt ashamed. To remember those traumas, it only it just makes me love my skin even more today. I wish I had been proud of it because I am today.

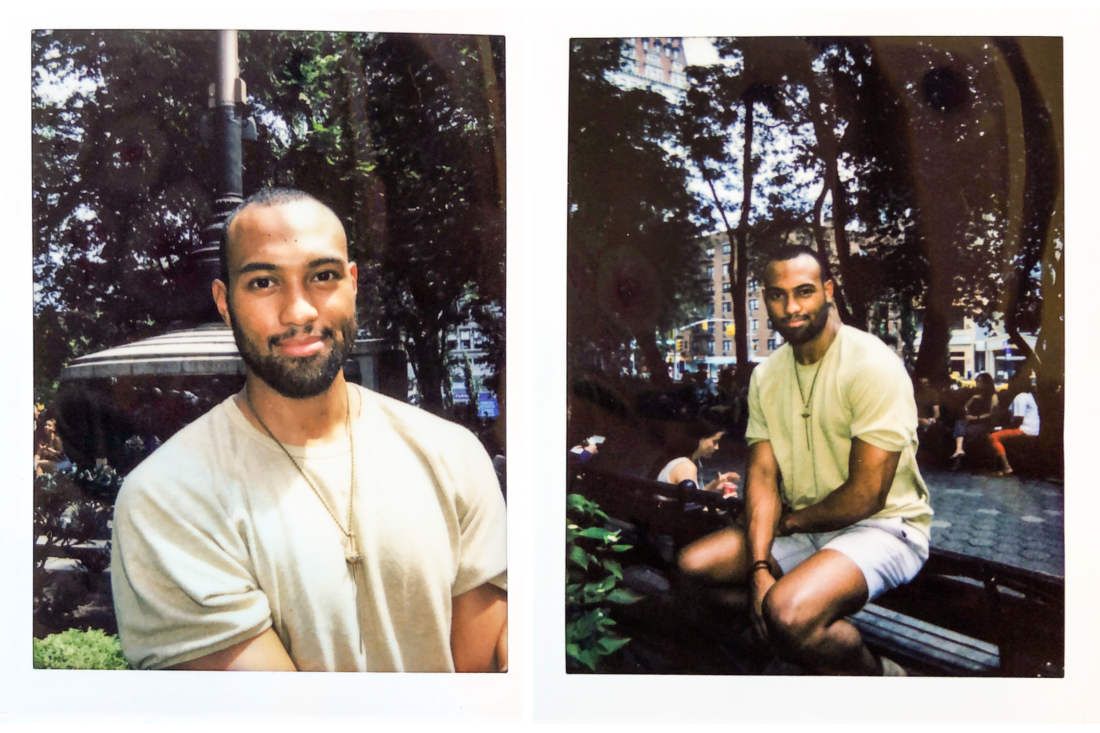

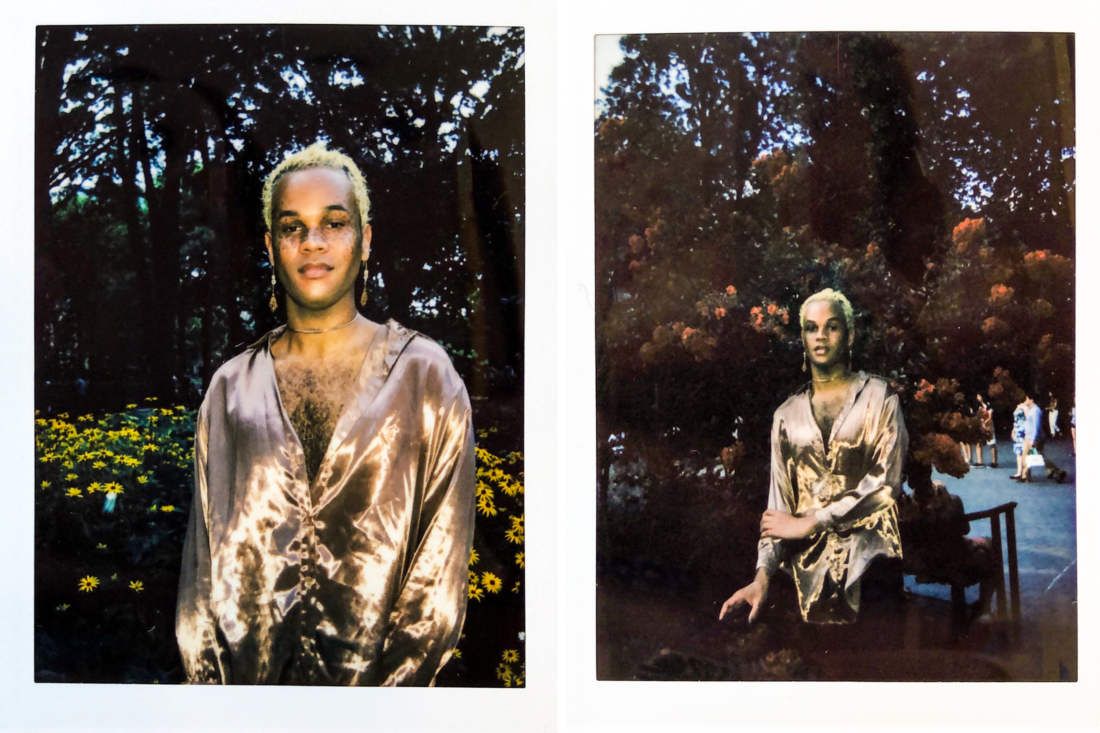

Adam, half-Filipino, half-African American

When I came to NY and started my career as a performer, there’s such an emphasis on your branding. But the world was telling me who I was and being someone with less representation it’s easy to be swayed to think that your experience isn’t valid.

In a world of tokenism, you don’t have the opportunity to show nuance, especially in the performing arts. You’re not able to show all aspects of what that person is because what you have there is a limited amount of exposure. That’s what’s so crazy about having entirely ethnic casts, you don’t have to play one type of person. You can have the villain and the hero be the same ethnicity, and you show a range of perspectives. The celebration of the Black Panther movement showed all these different types of people from the diaspora. I would love opportunities that provide mixed-race people to be represented in that way, where they don’t have to choose one or the other, that they are worthy in all of their beings. Who knows what that looks like, but if we can continue talking about it, if we can continue saying, there’s a voice because it exists.

Being mixed, you have that responsibility … you are the representation of many things, of the future, of the past.

Being someone with less representation it’s easy to be swayed and think that your experience isn’t valid. That you go with the status quo. I think as crazy as these times are, it’s waking us up to realizing how much of our culture is antiquated. How a lot of latent prejudice has been allowed to fester and take the forefront and be a part of our status quo, but it doesn’t have to be.

We talk about globalization as this thing, this buzzword, the future, and that’s really the story of intersectionality. Until we can truly claim that, and how we’re all responsible, then there really isn’t freedom. Being mixed, you have that responsibility, you are the token of it, you are the representation of many things, of the future, of the past. When we can figure out what belonging is in that place then we’re onto something.

Nelsan, half-Japanese, half-British

When I was younger, I was way more self-conscious about being ethnically mixed. I’d see people who are full-Hispanic or black or white, but not many mixed people. I felt a little weird growing up, but I realized being mixed is cool and I embrace it.

I’m way more in touch with my English side because of the language barrier. I don’t really speak Japanese, and all my extended family is in Japan or England. Growing up, I’d visit England more often because my mom is pretty separate from her family.

I felt a little weird growing up, but I realized being mixed is cool and I embrace it.

Now I’m trying to embrace more of the Japanese side. I’m learning Japanese on Duolingo. I’m going there in the spring. I’ve been once before when I was 4 years old but that doesn’t really count. I’m trying to be there for a month to absorb as much as I can.

Justin, half-Lithuanian, quarter-Puerto Rican, quarter-Crucian

Growing up in these times, with Trump trying to prevent America from becoming more diverse, has opened my eye to see what’s really going on, especially with black people getting killed for nothing. Just being black and breathing. Being mixed gives me a better platform to speak because a lot more people would listen to me. They really blow it off when it comes to dark skinned people talking about this issue.

But I am hopeful, because the generation I’m in is a lot more open than other generations.

That’s sad to me. A lot more people give me attention and that’s a privilege I have

But I am hopeful, because the generation I’m in is a lot more open than other generations. There are a lot more outlets for LGBT PoCs. That show Pose is beautiful. That’s an issue that’s actually getting a lot better. A generation before us, the LGBT community was not as accepting when it came to POCs. Whereas, in this generation it’s like okay, and? Anything else? It shouldn’t matter, but it does because it’s a problem still. I’m waiting to see the next up and coming generation. Hopefully generation to generation, these issues dilute and matter a lot less. That’s what I’m hopeful for.

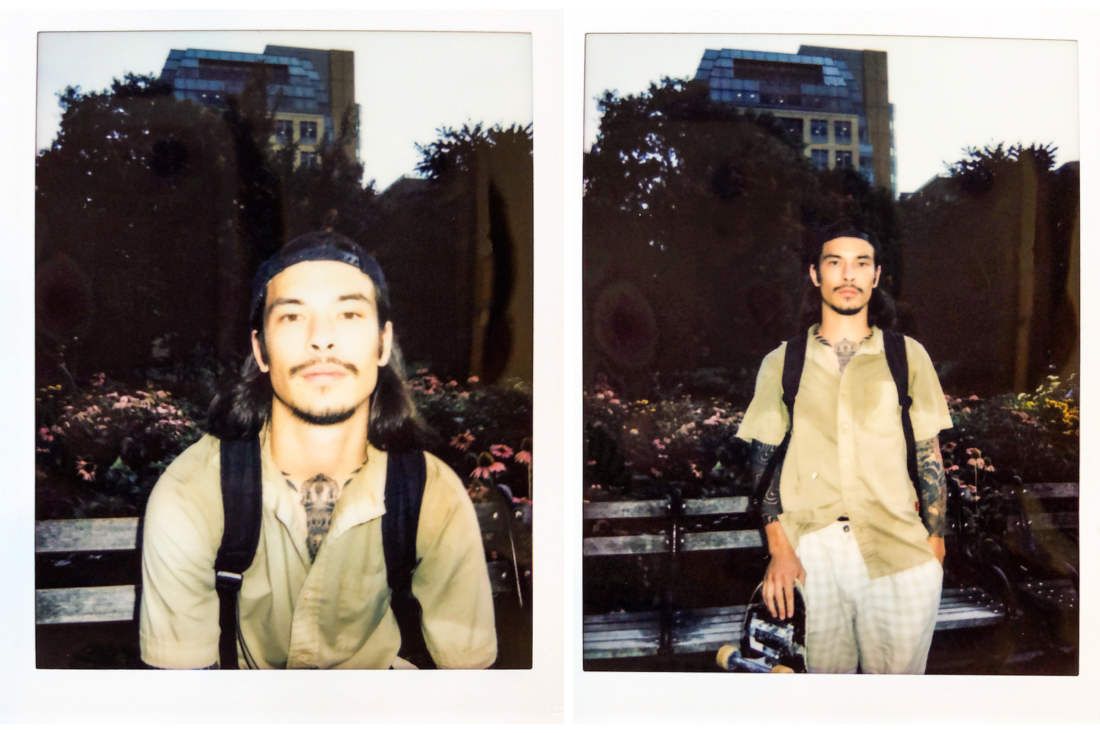

Sho, half-Japanese, quarter-Hispanic, quarter-European

I was in Japan until I was 18. I grew up in the extreme countryside. Imagine a country town of Ohio, but in Japan with rice fields and farms. That’s where I’m from. There really weren’t any other foreigners aside from my family, maybe one other family that was my dad’s friends. It was definitely an interesting experience. I never really encountered a problem, but there was teasing. Nothing intense, but people saying things, calling you things. You might know about the word “gaijin” (Japanese derogatory term for foreigner). I got that so much.

They [Japan] have a huge Western idolization so a lot of people were jealous with the way I looked. I wasn’t that happy with how I looked though because all my friends looked different. I was around 11-years old when I realized the difference in features. I had a crush on this boy, well it was a little bit of a crush, and I also wanted to be like him, look like him. The cheekbones were different, lip shape was different eye shape was different, he had a monolid and I had a double eyelids. I remember one time thinking that I wished I had a monolid so I could look more like my friends.

We have a term in Japan called “hafu.” I think that word is really dangerous because people might start to identify as half a person and not feel like they fully belong.

After a certain point, I got over it. That’s just part of growing up. But the biggest, hardest part was just not really getting accepted as a full Japanese person. We have a term in Japan called “hafu” so I was always half-Japanese and would would treat me like half-Japanese. I think that word is really dangerous, actually, because people might start to identify as half a person and not feel like they fully belong.

Personally, I don’t identify myself with race and I like that. I feel like that’s the future, you know? Hopefully, everyone is going to be somewhat mixed. It’s going to be more normal to the point where people stop talking about race and judging people based on race. All these racial issues, hopefully that’ll end. I feel like I got a head start. I’m not judging people based on what they are because I don’t do that to myself.

I’m proud to be everything that I am. Being mixed race is a beautiful thing and everyone should embrace it.

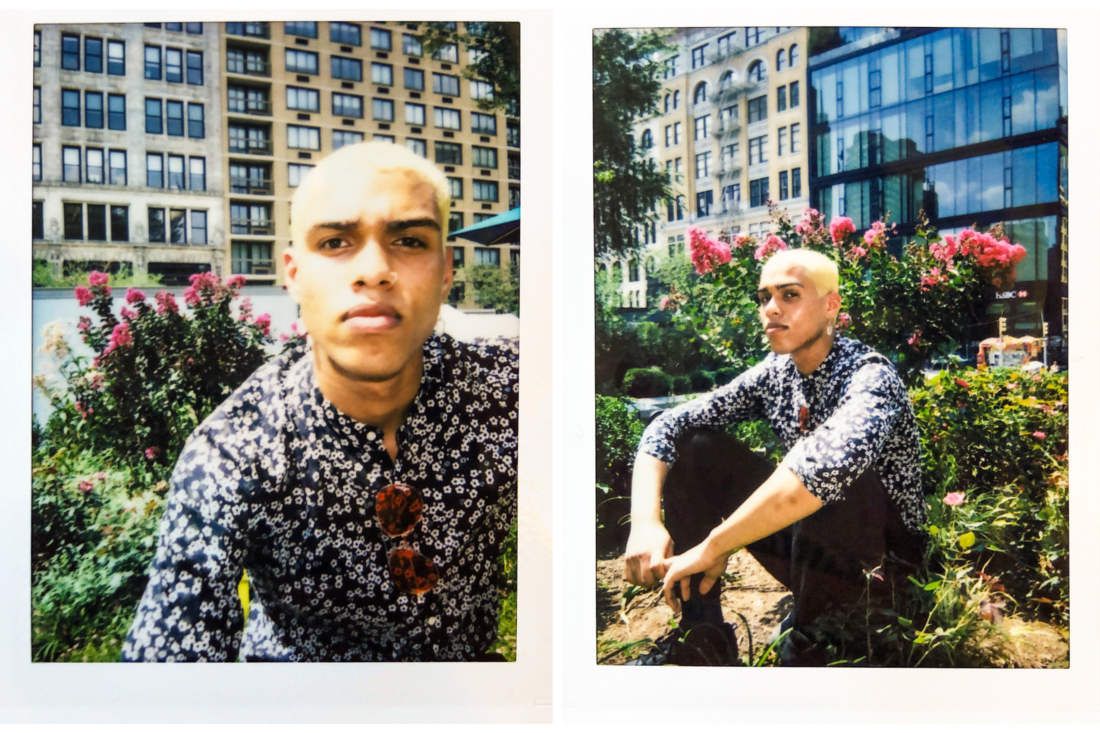

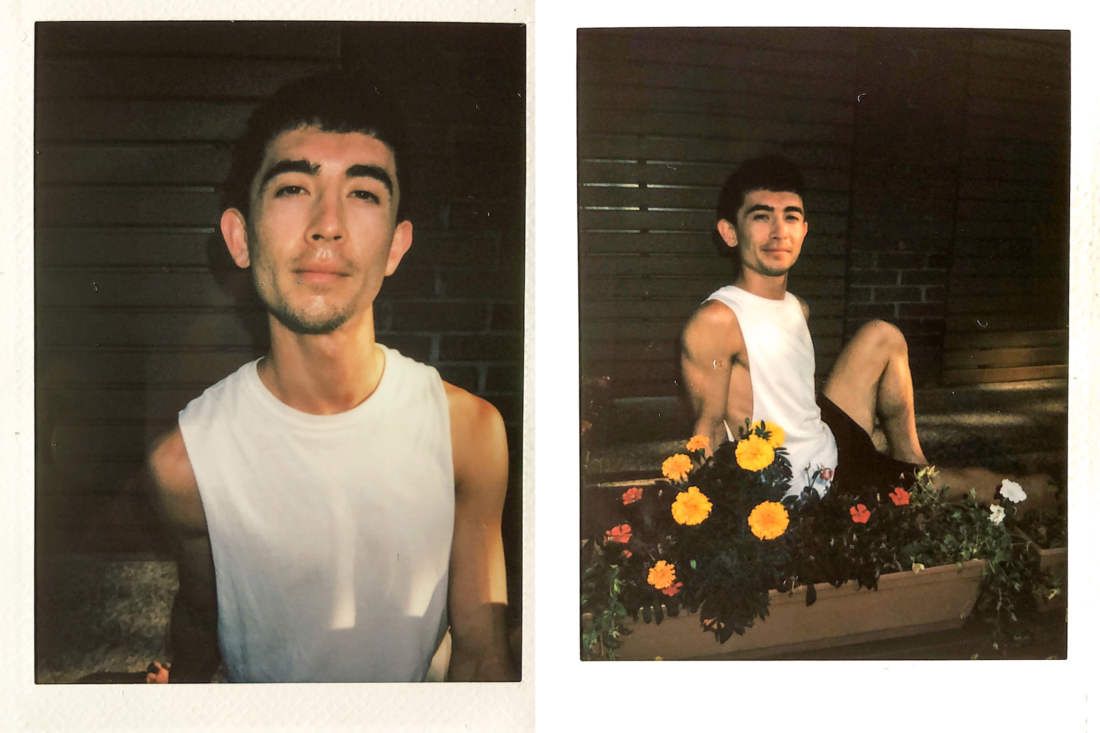

Aleck, half-Finnish, half-Venezuelan

The American Dream was such a strong idea when my dad moved here and I feel like that’s the case with a lot of parents who immigrated from Latin America. They don’t speak Spanish because they want their kids to speak English and assimilate into America. My dad played by those rules and didn’t share his culture with me because he wanted me to be American. It hurts because it’s a huge part of me. Luckily, my boyfriend is from Colombia so he’s been introducing me to a lot of things I don’t know, like food and linguistics. The other day we went to Union City to this crazy Colombian restaurant and everyone was speaking Spanish to me. I was like, “Wow people actually view and know me as Colombian and Venezuelan.” It was nice feeling included.

Although my skin is brown against white people and white against brown people, it’s still light enough to be white-passing. And I’ve definitely benefited from that privilege.

When it comes to fitting in, it can be really confusing. I’m white-passing but I can also have experiences like that one with my boyfriend. Being able to float between the two worlds can be very confusing at times because you can exist in both spaces but never feel like you belong. That’s why I’m in New York, where I’ve found my community through friends. I don’t have to think about existing as one or the other, I’m just who I am. And that’s special to me.

After moving to New York was when I also first recognized my privilege. Although my skin is brown against white people and white against brown people, it’s still light enough to be white-passing. And I’ve definitely benefited from that privilege, at least in the sense of not being discriminated against. Now, especially in the photo community I’m in, I make it a point to talk about privilege and related issues. I call people out when it’s necessary. Even if they’re “woke” they might be oblivious to some aspects of their privilege. My voice isn’t as powerful as someone who’s a minority and gone through discrimination, so if I can, I’ll give them the platform to speak about their issues.

Wataru, half-Japanese, half-Italian American

Japanese people will treat me as hafu (half Japanese, half white). They recognize there is a mix, but it’s never a negative reaction. In America, I’m seen as full Asian. People tend to treat me as full Asian, and there’s a privilege in that.

People tend to treat me as full Asian, and there’s a privilege in that.

When you’re mixed, people don’t know what to do with you. They don’t know where to put you, in a sense. And it’s not that I’m saying, “Let me take all those stereotypes, I love it!”, but it helped to make friends. In being Asian-passing I was better able to find community.

Andy, half-Cuban, half-German

Both my parents are Dominican but my mom’s side is Cuban and my dad’s side is German. Since both my parents were born and raised there I consider myself Dominican, but everyone else thinks I’m white. I lived there [Dominican Republic] for 6 years and people would ask me, “Why are you here? You’re white.” When I start speaking Spanish, that’s when they’re surprised.

“Why are you so shocked? Dominicans come in all colors!”

I remember a few weeks ago I went to this casting. They asked where I was from and I told them I was Dominican. They were all shocked. I was like, “Why are you so shocked? Dominicans come in all colors!” They loved the fact that I was Dominican but didn’t look it…that was weird. There still isn’t as much diversity in fashion. Everyone wants that Poseidon, God-looking guy. This super straight macho type that’s tall, defined, and white, obviously.

I’d love to tap more into my German side. I know that I have family there that I’ve never met. They know of my family here, too, but we’ve never connected. I want to live there for a year and learn about the culture and history. I’m really into history and I feel like that’ll allow me to know more about myself.

Ben, half-Chinese, half-white

My mom’s parents emigrated from China and she grew up in rural Minnesota. She had an intense struggle with her Asian identity; she was bullied. Because of that, she raised us to integrate into a white community. I wish that she’d fostered deeper community ties since that’s such a central part to current reclamations of identity.

Queer POCs are pushing the boundaries of our own understanding.

I still am a person of color and inhabit that sort of subjectivity, but I feel very detached from what I conceive of as an Asian community. But I do feel like a part of a community of POCs here in Brooklyn.

Queer POCs are pushing the boundaries of our own understanding. We are mixed but I think that could mean something new outside of an oppressive history, and that’s what our community is doing. I feel like that’s where I can contribute in terms of my racial identity.

Koji, half-Japanese, half-white

I think more conversations should be about the individual and what their experience is, more so than being able to label it all one thing. I see that with conversations about being Asian. Asian is so many different things, its a huge continent. In many people’s mind’s Asian is associated with East Asian so South and South East Asians can feel left out. Every person has their own unique experience so listening more to those. I’d like to hear more about what it means to be mixed race.

When meeting strangers, I wonder, do they see me as Asian and react that way? Or is it white? I don’t always know how they perceive me.

For me, it’s been cool to have two very different points of reference to think of who I am. It’s also given me empathy with more communities. Within the Asian community, I try not to be that loud of a voice. I know that it’s also my space and I can have a voice, but I don’t feel comfortable being the loudest voice in the conversation. I’m Asian in some ways but also some people are more Asian than me. And that’s truth.

I’ve definitely had privilege growing up because I can pass in white communities easier. But I don’t know how often that was the case. I know that some people perceive me as Asian. When meeting strangers, I wonder, do they see me as Asian and react that way? Or is it white? I don’t always know how they perceive me. This goes for dating, too, where there’s prejudice against Asians. Literally on a dating app last week someone said, “Oh you look a little bit Asian”. I thought, “Ok, let’s see where this goes…”

Merlot, half-White, half-African American

It’s funny, I just did my 23andMe results. My mother is both Irish and from the UK, and my father is African American. He’s mostly of Cameroonian descent with some Ghana and Ivory Coast mix.

I actually grew up only with my mother and her side of the family. For me, it was othering because I didn’t see representation in my household. I wish people would understand that being the black child to a white parent doesn’t mean you didn’t experience racism in the house.

Having a child that’s a different color from you doesn’t absolve you from racism, nor does it absolve the people around you.

A lot of people would say, “Your mom had you, the family couldn’t have been that bad.”

It’s not that I went through hell, but it was still there. Having a child that’s a different color from you doesn’t absolve you from racism, nor does it absolve the people around you. Taking into account your loved ones and the people you care about, calling people out and protecting them is important. Also, learning the culture. People who adopt or have mixed kids need to learn about the ways to take care of the child’s hair, how to properly moisturize. It’s so trendy in 2018 to have a mixed kid. Interracial couples are at an all-time high. It’s fun but people don’t do the work. I’m not saying you can’t have a mixed kid, but I wish people would do more research.

Kai, half-Japanese, half-white

Japanese culture was a big part of my life growing up. I was born there and my mom’s side of the family lives there so we’d visit pretty often. And although my dad’s American, he spent a number of years studying and working in Japan so my family as a whole was pretty Japanese-heavy. When I was 2-years-old my family moved to the Bay Area, which has a huge Asian American population, so I never had too much trouble fitting in or making friends. It wasn’t until I became an “adult” that I started to notice the nuanced differences between myself and others.

I want to use my voice to elevate others, to support my community, and most importantly, make others feel that they belong regardless of their background. If just one person feels empowered from reading this, I’ve done my job.

In America, it’s all about self-promotion, almost to an aggressive degree, which is the complete opposite of how Japanese people present themselves. I remember realizing this first in a work setting where those with the loudest voice would be heard. Then came the understanding of how Asians and Asian Americans are emasculated here, which on top of my queerness and femininity, led me to believe that privilege was something I lacked.But in talking to these diverse guys and carefully examine my life up until now, I’ve internalized that I do and have always had privilege. Maybe I don’t have as much as a straight, white man, but as someone who’s lighter-skinned and biologically male, I have a decent amount. And in that, there’s a responsibility. I want to use my voice to elevate others, to support my community, and most importantly, make others feel that they belong regardless of their background. If just one person feels empowered from reading this, I’ve done my job.