“Well, since you’re Native American, you must be able to attend college for free, right?”

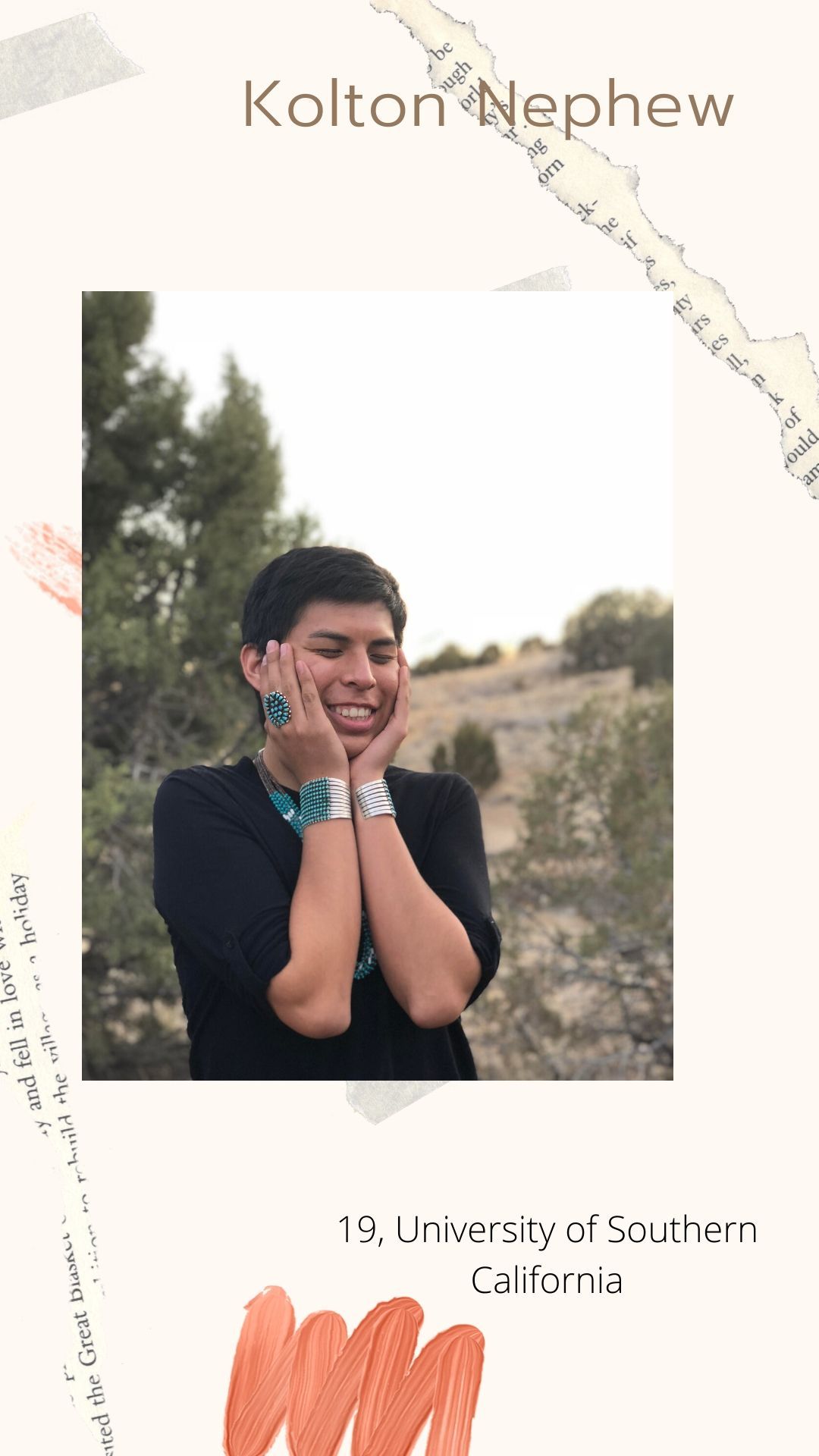

As one of the first to attend college – I’m a freshman at the University of Southern California – I remember that I’m making history in not only my family, but my tribe.

SEE ALSO: As a young Navajo, this is what it’s like in America

It makes me remember the stories of my paternal grandparents, my nalí hastiin and nalí asdzáán, both who tell me of their time at American boarding schools. They received trauma that would still scarred them today when white teachers and dorm assistants whipped and beat them, often for offenses like speaking Navajo or not being able to respond in English. It was their punishment into self-hatred for being “Indian.”

This generation of trauma still lasts today. While the national average of U.S. high school students pursuing higher education is over 60%, only 17% of American Indian/Alaskan Native high school students even continue their education past high school. Even if American Indian/Alaskan Native high school students attend college, they still face far greater challenges opposed to other students that are overlooked by institutions. Consequently, we as Native Americans/Alaskan Natives only comprise 1% of the undergraduate population in the entire country, it is infuriating to say that we are the last thought of in higher educational institutions.

Speaking from personal experience completing my first semester at USC, I am able to see these facts come to life. We are a small community comprised of about less than 20 Natives that attend a predominantly white institution, one that neglects our presence. Even though we are part of the Native American Student Union (NASU), this institution chooses to label us as a club instead of a minority organization based on our low numbers. But what they do not consider is why there are such low numbers in the first place. They fail to acknowledge the historic traumas, institutional racism, and educational prejudice that not only affect USC but institutions across the nation.

Although these statistics seem discouraging, it doesn’t paint the entire picture of our Native American people. Unlike common assumptions, we do have aspirations to go out, earn degrees, and explore the world beyond our reservations. At the core of our passion is to return to our people and make positive change. In different fields of occupations, we feel it is our duty to go back home, help our people and reservations, in the hopes that we can compete on the world stage. We’re still here and not just trapped inside your white-washed history books.

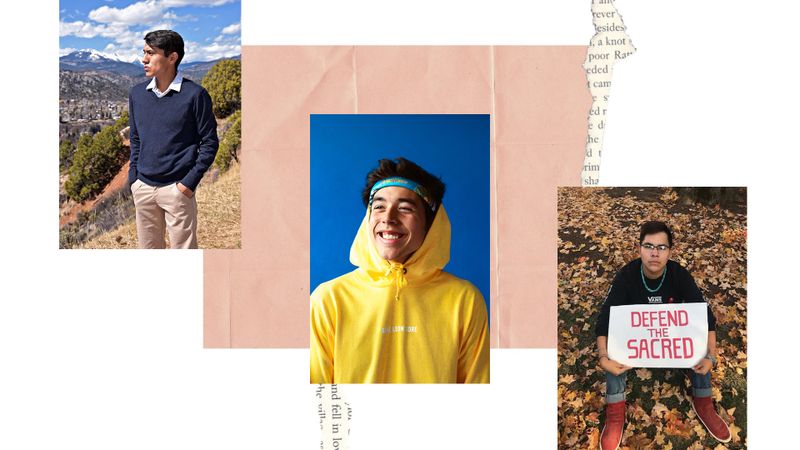

To further reflect the end of this first semester of college, Very Good Light asked Native American students attending institutions across the nation about what it feels like to be Native in colonized spaces. Here’s what it’s really like to go from the reservation to higher level institutions.

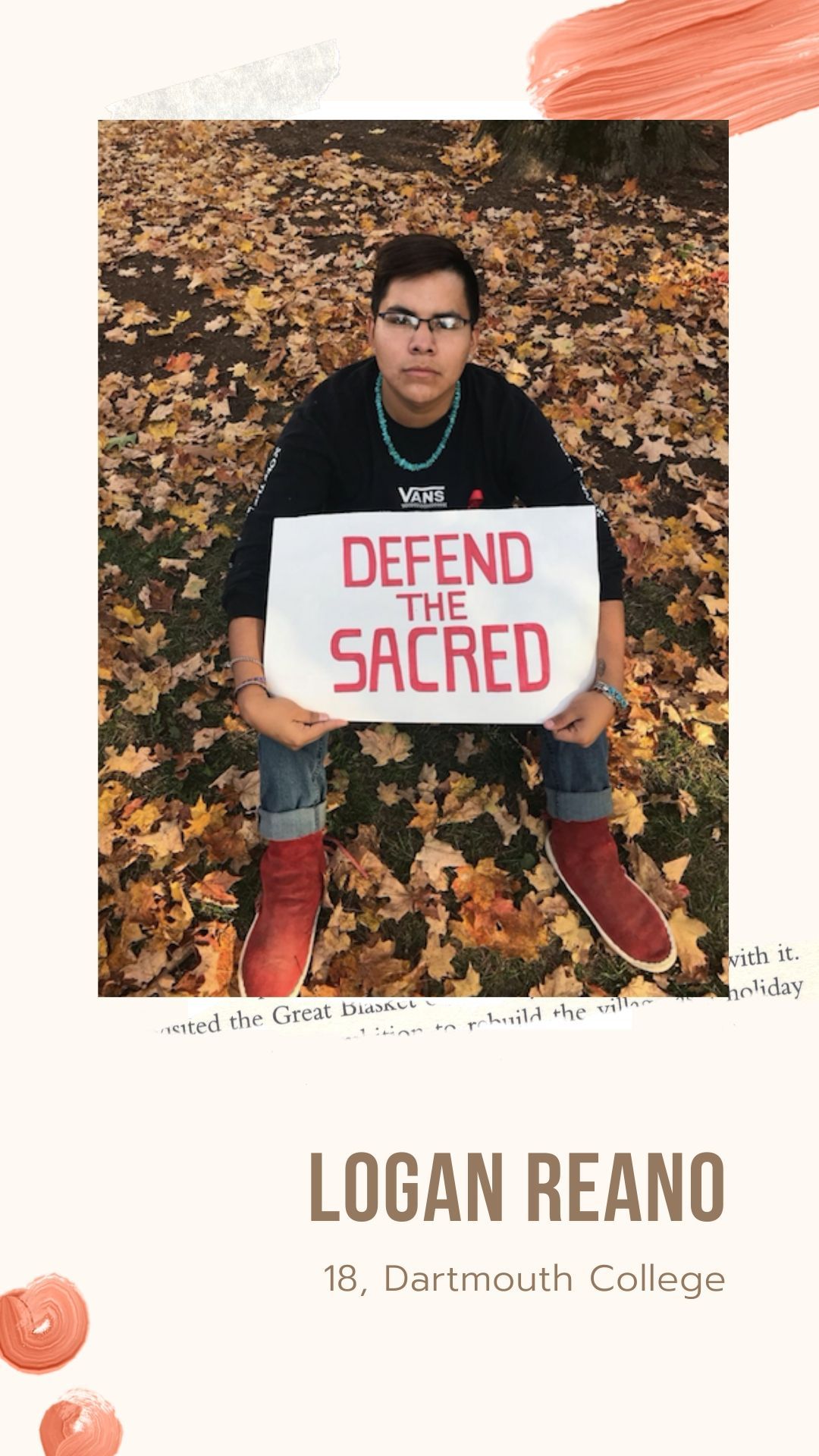

Logan Reano, 18, Diné, Kewa’meh, T’óynemą ,Thítȟuŋwaŋ (Navajo, Santo Domingo Pueblo, Taos Pueblo, Lakota Sioux), Freshman, Dartmouth College (Quinnipiac, Paugussett & Wappinger homelands)

Do you feel pressure to assimilate? If not, how are you preserving your culture while fitting into these institutions?

I decided to leave home to go to a school 2,000 miles away to receive a Western education in one of the most competitive schools in the U.S. I chose to get a Western education so that I could go back home to promote the wellbeing of the Navajo Nation. I want to go back to the Navajo Nation not to promote taking a place in said world but taking a place in their indigeneity.

Describe being Native American at your institution and the challenges you face?

Being Native American in a western educational institution in many ways can be crushing. These institutions were created and designed for wealthy heterosexual white men, so without a doubt being a gay, low-income, first-generation Navajo student is challenging. Even the thought of how assimilation still occurs is a constant struggle I face. This has led me to think why I am even going to college and in what ways that I can help Native Americans as a whole in these institutions—I am still looking for the answer.

In what ways can Native American male youth find solace in predominantly white college campuses?

As Navajo tradition dictates,when you leave the four sacred mountains (traditional Navajo geographic borders), you are leaving Diné bikéyah (Navajos Land) and its protection as it longs for your return. Using this cultural knowledge, it reinforces that my identity is deeply rooted in the Navajo philosophy and way of life in which I have found comfort in. It is the foundation of Navajo philosophy that provides me comfort in the white-dominate western culture of America.

How does all of this translate for the need of self-love for Native American male youth?

As a Navajo man, I turn to the Navajo concept of Hozho, which promotes self-empowerment and balance. Essentially, stressing the human ability to be self-empowered when practicing responsible speech, behavior, and thought. This allows one to maintain a healthy relationship with the universe. More specifically, the Navajo teaching of Ha Hozho emphasizes tending to the mind, body, and spirit to live a long and healthy life. Coupled with this teaching are stories I use to navigate my life, good or bad. It is both of these teachings that keep me motivated to complete my 4-year commitment to Dartmouth College.

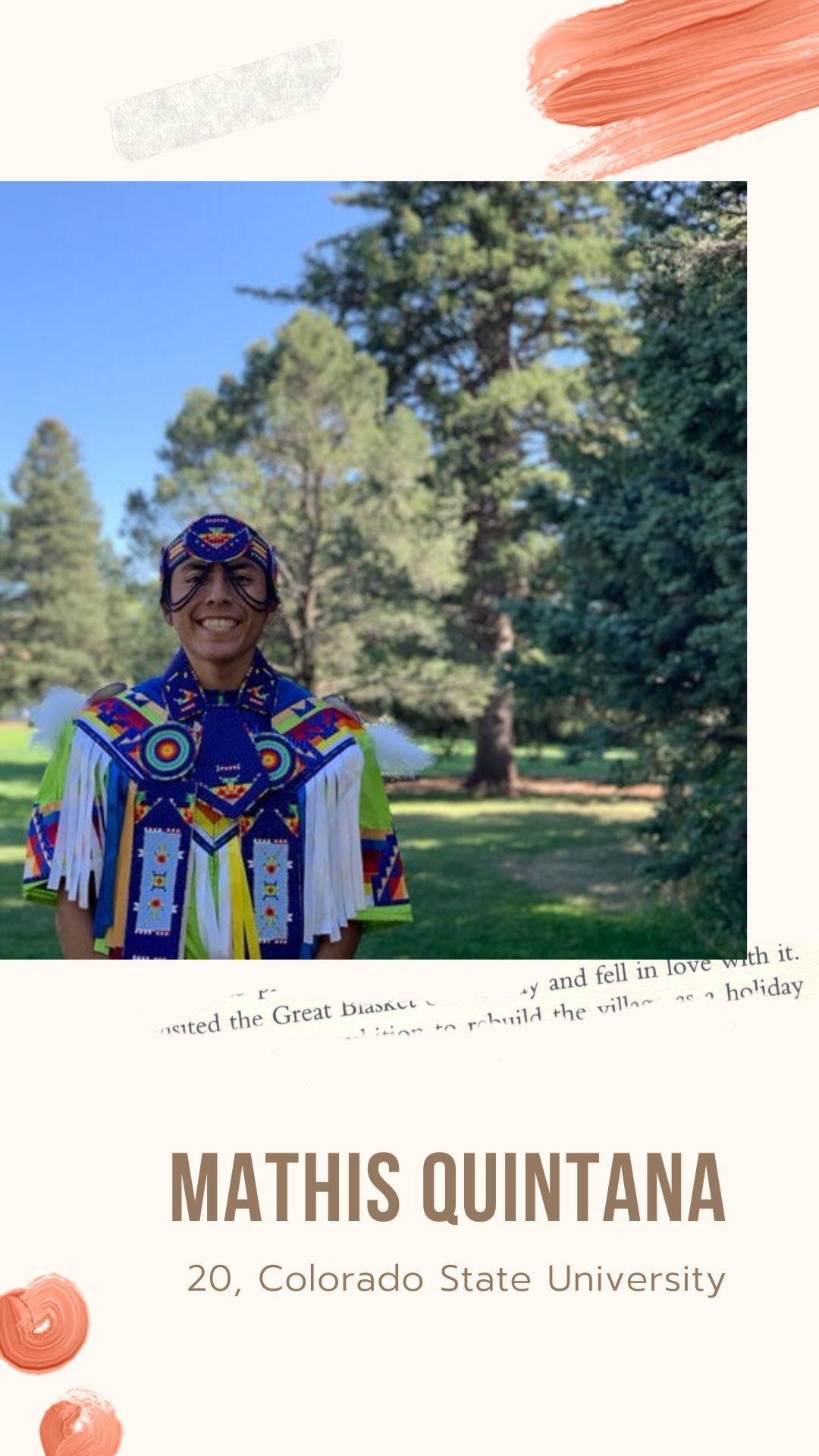

Mathis Quintana, 20, Abáachi (Jicarilla Apache), Junior, Colorado State University (Cheyenne & Arapaho homelands)

In what ways can Native American male youth find solace in this white America?

For me personally I find solace by surrounding myself with people who are similar to me. This may be family, friends, or just people that I get along with.

How has your perspective of the U.S. changed as you grew up?

Growing up, I never thought much about the U.S., I would just always root for the

them when I seen team USA in the Olympics. However, as I got older, I started to learn about the hostile relationship between the U.S. government and Native Americans. But it wasn’t until college I fully learned about the colonization and genocide that this nation used. Taking in this newly acquired knowledge, my perception of this country has changed. It makes me even more proud of my Jicarilla Apache culture and people because we are still here.

What is education to you as a Native American and how do you plan to use that in the future?

For me, education is being able to learn different concepts and ideas that would not be available where I am from. I take upon this secular knowledge learned to return back to my reservation and people to change the situation they face. Using this education, I want to be a friend and role model to the young men in my tribe, who can show that they are able to learn their language and culture while attending college. But honestly, I’m still figuring out what I want. Right now, I use my identity to anchor me and all I want is to make the transition to college easier for first-year native students.

Describe being Native American at your institution and the challenges you face?

On my campus, I can tell that I am not like everyone else. Sometimes it has been hard for me to feel like I belonged. However, once I connected with other native students, it felt better because we were both going through the same situation. Having the Native American Cultural Center at my school allowed me to have a sense of community is the reason why I am still in college. A challenge for me is making all the new native students feel like they belong here and I try and build relationships and community by putting together intramural sports teams.

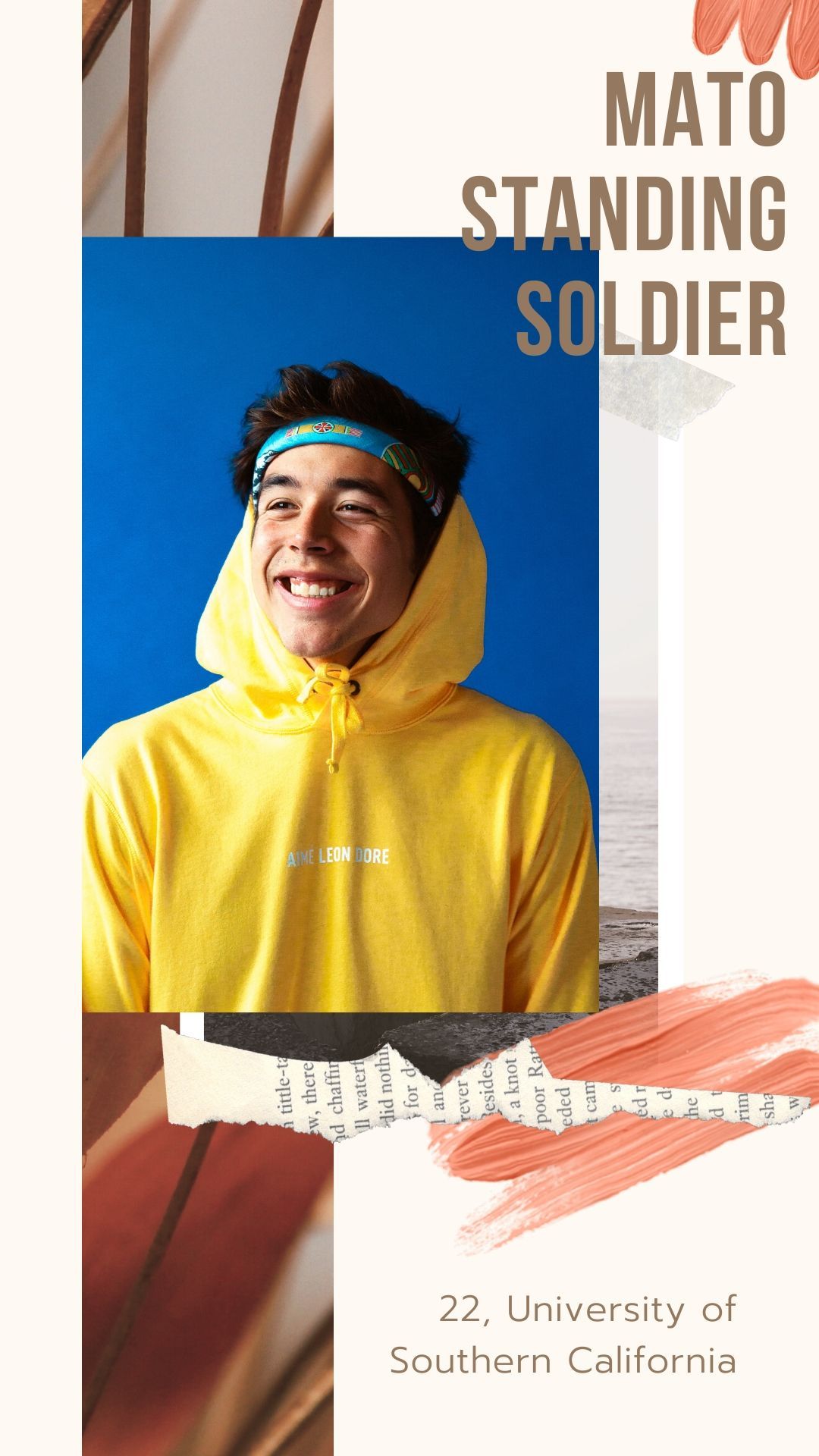

Mato Standing Soldier, 22, Thítȟuŋwaŋ (Oglala Lakota), Senior, University of Southern California (Chumash & Tongva homelands)

In what ways can Native American male youth find solace in this white America?

Ideally, Native men can turn to their peers, both men and women, for solace. There’s no set blueprint for finding refuge inside of a nation designed against you. But what helps me is finding those who benefit from my own self-empowerment. As a Native man, when I’m the best version of myself, other Natives and people of color benefit because I can support through leadership and gentleness in our journey towards liberation.

Do you feel pressure to assimilate? If not, how are you preserving your culture while fitting into these institutions (or not?)

The word “assimilate” slaughters the efforts of young Native people in this country. It’s also a powerful weapon of lateral violence against one another — the fight for who’s the most “Native.” When you accuse someone of assimilating, you’re really slighting their means of survival. Natives might reconsider themselves as acclimating rather than assimilating. That said, yes there is a tremendous amount of self-pressure to acclimate while preserving my culture. Everything I do and achieve is with that intention — a balancing act that I think many Natives endure.

What is education to you as a Native American and how do you plan to use that in the future?

Education is a magic wand that this country seldom grants to Native Americans. I personally don’t enjoy school at all because I can’t sit still, but I know it’s such a privilege that my ancestors were denied, so my education is dedicated to their sacrifices. I plan to use my education as a conduit for other Native kids to find whatever it is, they can excel towards. A goal of mine is to use the money I make from all of the music and films I create and fund scholarship opportunities for tribal youth around the globe. Education is supposedly foundational in this country, so I want to ensure my people are schooled.

What was the most eye-opening experience going into a 4-year institution?

How lonely it would be all be. It’s the great irony of college: why is that so many people, who are all the same age, en route of obtaining the same goal, feeling so isolated from one another? I’ve had some fantastic experiences at USC, but the most eye-opening aspect was the loneliness component.

Kalvin Benally, 20, Diné (Navajo), Sophomore, Fort Lewis College (Navajo & Ute homelands)

In what ways can Native American male youth find solace in this white America?

Some ways I feel Native American male youth can find solace in White America would be to confide in their tradition, friends and family.

Do you feel pressure to assimilate? If not, how are you preserving your culture while fitting into these institutions (or not?)

I do not feel the pressure to assimilate for I only surround my around with people who are positive influences and good for my well-being. I’m preserving my culture by practicing my traditional teachings such as: Ahééh Jinízin (be appreciative and kind), Há Hózhó (show positive feelings toward others), Dóó hwił hoyéedá (Don’t be lazy) and T’áá hwó’ají t’éego (It’s up to you). These teachings keep me on the right path and remind me who I am and where I come from.

What was the most eye-opening experience going into a 4-year institution?

The most eye-opening experience going into a 4-year institution was the concept of being alone. Starting off you’re all alone, your friends are going to different colleges in different states. Your go-to friends are busy with their own lives and your family is hours away. Soon, loneliness creeps up and piles enough sadness to make you want to drop out. I realized that being alone is okay because then you are able to enjoy your own company and that makes you stronger, that makes you never rely on another person company for happiness.

Describe being Native American at your institution and the challenges you face?

At my institution, being Native American is not an abnormality due to the high number of native students that attend. However, one challenge I have faced is the constant stereotypes that non-native students label me due to the tuition waiver I receive from my school for being an enrolled member of a federally recognized tribe. They throw jokes that attack our identity because they blindly see it as us receiving free college because we are native. However, they do not consider the brutal history my people and other Native Americans have faced in order for institutions to grant us such privilege and to ease the transition for native students to attend college.