Two years ago, a bill passed allowing for legalization of CBD across all 50 states. Seemingly overnight, CBD became the cash cow of the wellness industry. CBD-infused products began pervading big-box retailers such as Sephora; CBD subscription boxes run up to $170 a month; even GOOP-esque Fleur Marche soon offered an ‘Extra Strength CBD Creme Set’ for $120. By 2022, CBD is estimated to rake in over $22 billion dollars.

SEE ALSO: Black men are showing us how skincare is done

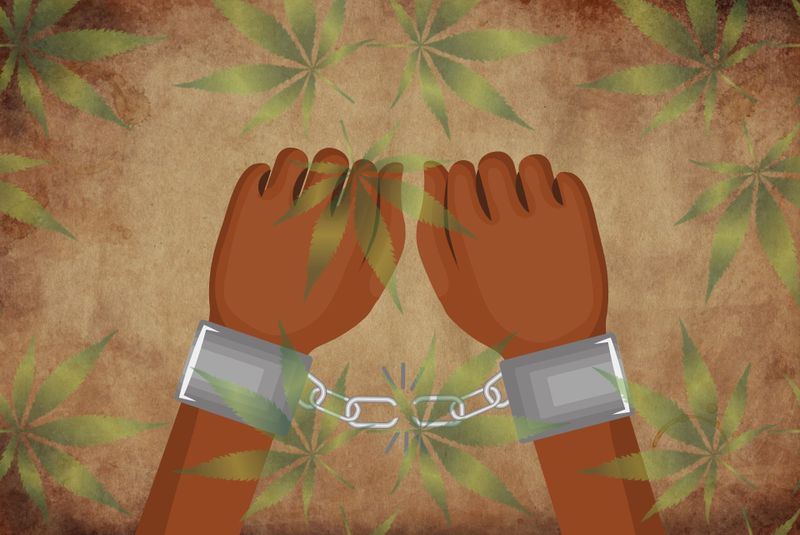

Between the CBD boom and the annual celebration of cannabis culture every 4/20, it’s been easy to forget the dark roots of the marijuana industry. When Mexican immigrants introduced American culture to marijuana, it became known as the “Marijuana Menace.” Government officials in the Nixon Administration have admitted a marijuana crackdown served to “undermine black communities and fragment the political left.” Cannabis-related arrests silenced many involved in the Black Panther and Civil Rights movements and also Anti-War advocates. And then there was President Reagan, whose 1986 ‘Campaign Against Drug Abuse’ and ‘Anti-Drug Abuse Act’ skyrocketed incarceration rates.

“Officers arrested more people (predominantly people of color) for minor marijuana offenses,” communications scholar and culturist Dr. Melvin Williams tells Very Good Light. “It ignited what was coined as ‘dramatization media bias’ toward marijuana. Soon after, the media became obsessed with characterizing cannabis use as deviant behavior.”

The war on drugs spent approximately $1 trillion on drug arrests – and vilified communities of color in the process. Since the 80’s, the number of people arrested on drug charges has tripled, with Black people four times more likely to be incarcerated than white people. Black people arrested on drug charges serve almost the same amount of time a white person does for a violent crime. And while communities of color have been jailed for cannabis-related incidents en masse, for America’s white population, marijuana possession has mostly meant profit. In fact, in 2017, a study showed 81-percent of dispensary owners were white.

Entrepreneur Rickey Colley, was arrested at age 18 after stealing cars for parts to feed his younger brothers after his drug-addicted mother was unable to support the family. Post-release he began sending weed in envelopes to a friend he had met in prison who lived in Detroit. Soon, he had “graduated to sending [marijuana] via tractor-trailers.”

Rickey was serving 72-months behind bars when his sentence was commuted under the Obama administration. While he appreciates his earlier release, he can’t see the government’s approach towards marijuana and people of color shifting anytime soon.

Since the ’80s, the number of people arrested on drug charges has tripled and Black people are four times more likely to be incarcerated compared to whites.

“If those new marijuana laws can help bring families back together faster and decriminalize it that’s great,” he says, “[But] as far as all the initiatives, they have in place, marijuana is [criminal] in their book no matter how you slice it, so any relief in my eyes is reparation.

To its credit, the CBD industry has acknowledged marijuana’s nefarious past. Illinois’ ‘Restore, Reinvest’ program supports low-income individuals of color in areas affected by the war on drugs to open up their own dispensaries. The ‘Renew’ Program in California, also referred to as R3 and Los Angeles’ Social Equity Program, prioritizes applications to people who have been negatively impacted by criminalized cannabis.

Laneisha Edwards, a Los Angeles resident, applied and was accepted into the Social Equity Program. “Two of my younger brothers were murdered, one in 2010 and one in 2016,” she tells us. “These events effectively changed my life, and I am now an activist who believes in advocating for our neighborhoods.

“I saw opening a dispensary as an opportunity to give back to my community by offering job security and job placement. Also, as a single parent, it would create stability from living paycheck-to-paycheck and will allow me to focus on continuing to advocate for my community.”

Despite the government’s good intentions, Laneisha says the program falls short in its mission to make real reparations for minorities. She describes the process of trying to open up her own dispensary as “extremely stressful” and particularly difficult to navigate without a strong business background. Still, her hope won’t waver.

“There have been plenty of moments where I felt like stepping back, but for many of us is an opportunity to create generational wealth for our families and our employee’s families,” she says. “This opportunity for people who grew up in low socioeconomic communities only comes once in a lifetime. There is no giving up.”