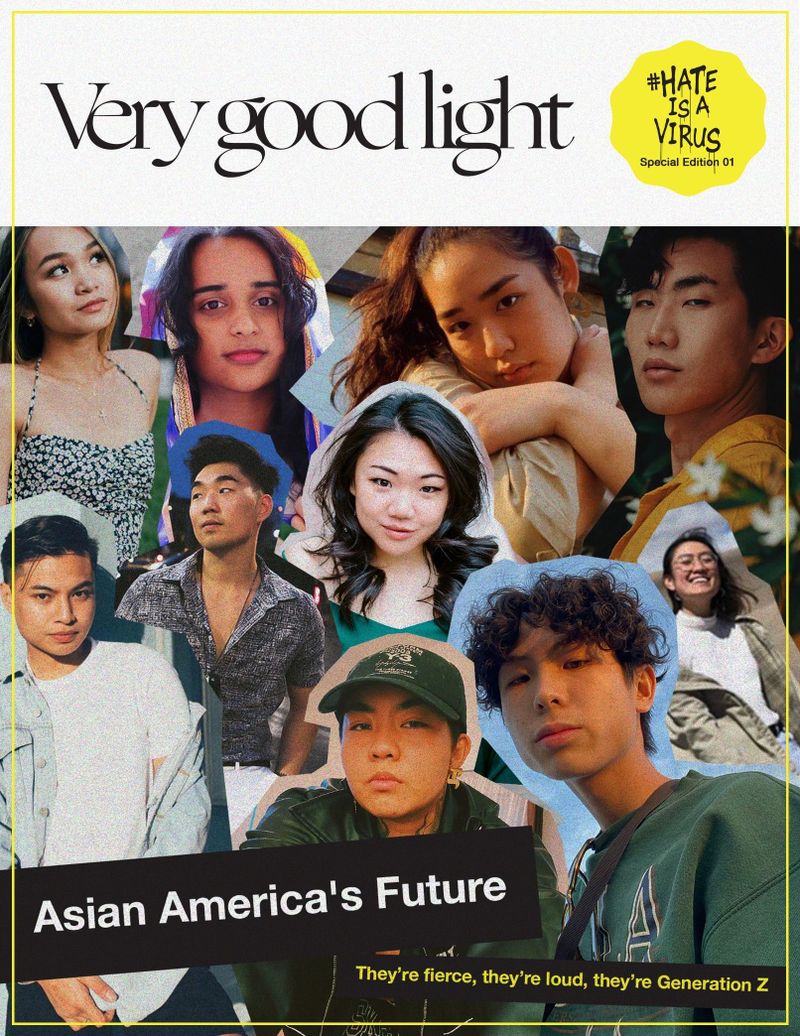

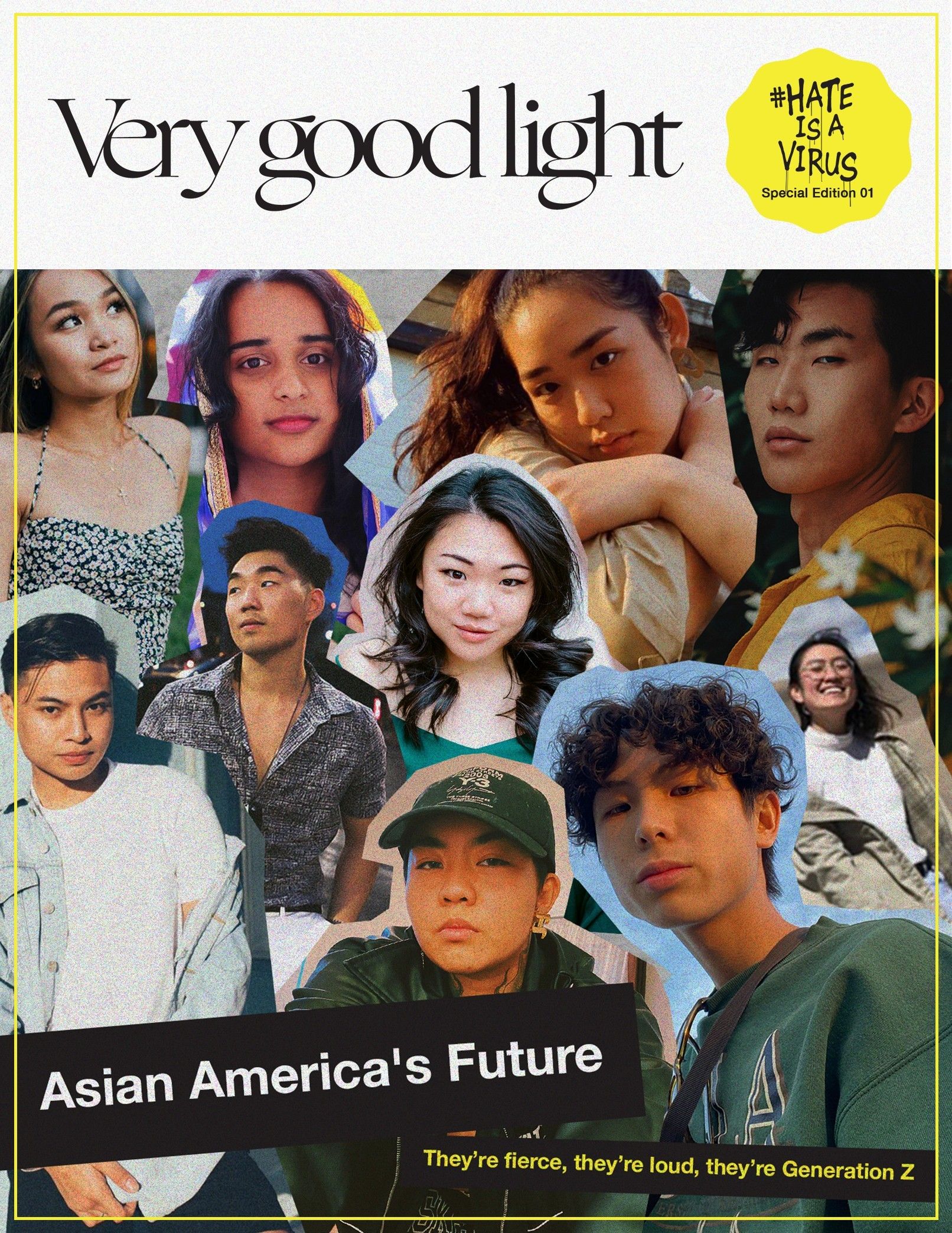

May is officially Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, celebrating the journey of Asian Pacific Americans, what they’ve accomplished, and what’s to come. For an entire week, Very Good Light is kicking off a series of Asian American stories, highlighting the future of Asian America. From Generation Z activists, healthcare workers on the front lines, music artists, and more, we’re uplifting Asian stories. We’ve partnered this week with Hate Is A Virus, a grassroots campaign that aims to raise $1 million to businesses affected by COVID-19. Together, we hope to spark conversations, change, and community. After all, the Asian American experience is the American experience. We’re in this together. For more on Hate Is A Virus, go here.

They’re fierce, they’re loud, they’re Gen Z.

In 2020 Asian Americans have become the fastest-growing population in the US. Which means the power is in the hands of Generation Z. After all, they’re the future of politics and will become a major segment of eligible voters. The Asian American population has seen immense growth in the past two decades, growing 139%, larger than any other major racial and ethnic group.

Politics aside, Asian Americans are the undeniable trendsetters in America. A Nielsen study found that Asian Americans are the firsts to adopt devices and digital trends. Which means yes, TikTok, a Chinese company, was used by Asian American en masse, first – then adopted for Americans later. With a collective $986 billion in buying power, this demographic is only quickly growing.

All that being said, it’s clear that Asian Americans are more relevant than they’ve ever been. But as we’re seeing Asian Americans rise in power, we must reflect on their collective pain. Sadly, we’re seeing a spike in hate crimes towards Asian American communities, one where there are up to 1700 reported each day. Though lamentable, it’s nothing new. Asian Americans have always, always faced pushback. This, starting with Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which was the first immigration law recorded that excluded an entire ethnic group.

SEE ALSO: Being Asian American means that you’re always enraged

Three years later, many Japanese, Korean, and Indians began to arrive in America. The act of categorizing India as a “Pacific-Barred Zone” country is described as “Hindu Invasion,” one that made it near-impossible for Indians to immigrate with white Americans fearful they were taking over.

In 1924, all Asian immigrants excluding Filipino ‘nationals’ were denied citizenship; naturalizations and were banned from owning land and marrying a white person. Asian Americans were seen as, “threatening, exotic, and degenerate.” During World War II, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Japanese Internment Camps were built primarily on the West Coast separating hundreds of thousands of families. Leaving a lasting impression that has affected the Japanese community to this day.

But thanks to the Civil Rights movements led by black Americans in 1965, there was a lift on bans and 20,000 immigrants from each country would be allowed in on an annual quota. This was the first time that Asians were able to come to America as families.

Like other PoCs Asian Americans’ strides and monumental efforts and triumphs in building this country into what it is today have been foreshadowed in History by their white counterparts. There’s also been erasure and invisibility when it comes to Asian American stories. Simply put: Americans have benefitted from Asian Americans’ contributions to this country and were built from the labor of all people of color.

With that being said, we’re seeing that generations later, Asian Americans are thriving. Through their collective pain, the new generation of Asian Americans is making strides to challenge the current narrative.

They’re loud, proud, unabashedly Asian American, and going nowhere. Here they are, in their own words…

Abe Kim, 22, California, Student, Actor & Model

Being an Asian American is living in various states across the country I’m still asked, “Where are you really from?” I feel like all the tribulations that I have faced solely from living the Asian American experience have challenged me to speak up for myself by doing what makes me happy.

Growing up in a predominantly white community, it didn’t take a lot for me to realize that I was a bit different from everyone else. It was as if my race was an open topic for discussion for everyone who noticed my presence, but when I stood up for myself, I was “too sensitive.” The worst experience was in high school when I finally entered the dating scene. That was the first time people would reject me solely because of my ethnicity. As a result, I started blaming and hating myself for being something that some people didn’t like.

With the rise of xenophobia in the current climate, I’ve experienced discrimination yet again. Before quarantine was put into place, I called a car through a ride-sharing app for a casting call, but once I got in the driver refused. He told me he felt “uncomfortable” to drive me. I tried to ask him why, but I knew with what was going on and the way he looked at me that it was because I was Asian. It was horrible and I felt shaken. Aside from my casting not going as well as I had wanted, I came home feeling like I had done something wrong; reminiscent of the feelings I had back in high school.

As a Korean American who can’t speak Korean fluently, I feel like I struggle with both identities all the time. But beyond not being able to have a full conversation with my grandparents, I have had a weird experience with not being “Asian enough” in America. I wanted to have Asian friends who understood my experience, but it was often rare for me to find anyone who sought refuge in their ethnic community after experiencing their own internalized-racism. Even though I sometimes feel like an outsider, that does not account for how welcoming other AA’s have been whenever I felt lost. Seeing other Asians being vocal about their beliefs online is a form of representation, promoting our identity that is often undervalued.

Like many other starry-eyed people who live in LA, I love acting as it’s my passion. Going to castings is very interesting. As you would have guessed, I don’t see many Asians. Some may say this is to my advantage, even so, it has been hard to land a job from modeling. The deciding factor may not be because of my race, but the feeling of possibly being the token Asian to fill a quota at castings is very real.

I am so grateful for those in the entertainment industry who have made time in their schedule to connect with me. This past fall, I had the incredible experience to intern at Saturday Night Live, which also happened to be the first season Bowen Yang appeared on the cast. Even though I was an intern, he was always open to answering any questions I had about his career and gave advice about my own. I am so grateful to have made such a genuine connection that I believe wouldn’t be the same had we not been Asian-American.

I think it will take more than one generation to change the bias against Asians. I’m glad Gen Z has used the internet in such a revolutionary way where we are finally being taken seriously. In the future, I hope one day to not think twice about seeing an Asian on a show or movie. I hope more Asian Americans would challenge their community once it comes to its anti-Blackness. Although our experiences as AA are valid, I do not think we need to tear down another community to have our voices be heard; especially a community that has fought so hard for the rights of other people of color.

Pooja Mehta, 24, New York, Master’s Student & Founder of I Define Me

My Asian identity really came into play when I was diagnosed with a mental illness. The South Asian community is generally not accepting of mental health issues, and I was so scared of the response that I suffered in silence for two years. When my parents found out, they were so helpful and supportive, but even then I was told to keep my diagnoses a secret from my community. When I started speaking out about my diagnosis, I knew I was excluding myself from the community, and making myself the odd one out. But it has been worth it.

As an Asian American, you get the best of two incredibly rich cultures. I grew up taking both ballet and Bharatanatyam classes, eating both pizza and pakora, and listening to AR Rhaman and Adele. Sometimes, I do find myself struggling with both identities Asian and American – to me, I see the hyphen between Asian-American as a seesaw, and you’re trying to get it to sit just right. Every time I am with South Asians, I feel like I’m too American. Every time I’m with Non-Asians, I feel like I’m too Asian. But lately, I have been more comfortable in that in-between space–recognizing that there is something unique and complex in my identity and that is something to be celebrated.

I distinctly remember when I was in first grade, my mom had made my favorite lunch–okra sabji and roti. One of my friends and I sat down for lunch, and when I took my food out, she started screaming about how gross my food was and how much it smelled. I was so embarrassed that I threw the food that my mom had spent so long making away.

Project: I Define Me is a project I founded that aims to reduce the stigma around mental illness by showing the person behind the disorder. People with mental illnesses are, first and foremost, people, and I aim to demonstrate that through storytelling. I was inspired to start this because so many times I would tell people that I have a mental illness and suddenly that’s all they would think of when they thought of me. I wanted to create a platform that allowed me and others to define themselves outside of our diagnoses.

Once I started my journey as a mental health advocate, I realized that the value of my voice was the fact that I came from a South Asian background. I talked about how my identity shapes me, my celebrations and doubts about it, and how that influenced my mental illnesses and my recovery journey. When I started speaking out, someone reached out to me and told me that by sharing my experiences, they didn’t feel so alone and were inspired to get help. That is when I discovered how important and valuable the work that I do is.

Being a child of immigrants, trying to balance these two defining aspects of my identity, and living with mental illnesses puts me in a space where my experiences are needed in the world. I promote the beautiful parts of my culture, speak out about the flaws in my culture, and work to make sure that the Asian American Identity, as it relates to mental illness, is one that is receptive and positive. I hope for a future of celebration for our identities and our cultures within the Asian American community. I hope for a future where we can be unapologetically ourselves, without the shackles of stereotypes. And I hope for a future of wellness, where trauma doesn’t get passed down through generations and where we can all thrive together.

Fynest China, 21, Hawaii, Digital Content Creator

The first time I went back to the Philippines, I was really able to reconnect with my cultural identity. The entire trip helped me reconnect with my childhood memories and I was also able to see how I used to live my life back then. When I moved to Hawaii as a child, it was never a challenge for me to balance my identities, because I still connect with my culture whenever I’m home by speaking Tagalog and eating Filipino dishes that my mom cooks. Growing up in Hawaii I was exposed to various cultures because it is a melting pot with a variety of different ethnicities and cultures. On the island, we have a variety of food places to eat, whether it’s Korean food, Chinese food, Filipino food, etc. A lot of people also speak different languages and are very open to diversity.

That doesn’t mean that growing up, I didn’t face challenges. In middle school, I went through a time where I was getting rid of my Filipino accent in order to try and fit in with the other kids. I got rid of my accent because I didn’t want to be made fun of by other kids. As a result, kids were nicer and less harsh to me when I got rid of it. Now, I wouldn’t care at all if I had an accent. Today, I’ve grown from these challenges. It is a process but I have been feeling confident and really working on accepting myself.

A way that I do that is by sharing a lot Filipino-related videos on my social media and I believe it’s a huge way to really promote my culture. I’m doing all of it for fun and to make people happy. Every time I meet or run into someone who knows me, I always cherish it and feel special from it.

Being an Asian American, I have a broader perspective and understanding of both sides. Having the knowledge to speak both languages is an advantage. Since I live here in the US, it is easier for me to communicate, and still be fluent in speaking my maiden tongue when I go home in the Philippines. I hope for other Asian Americans to not forget their culture.

Holding onto your culture/identity defines who you really are and you can’t really take that away from yourself no matter how much you try to do so. The connection will always be in you. No matter how insecure and emotional I may get, at the end of the day, I still know who I am. And that person is unstoppable.

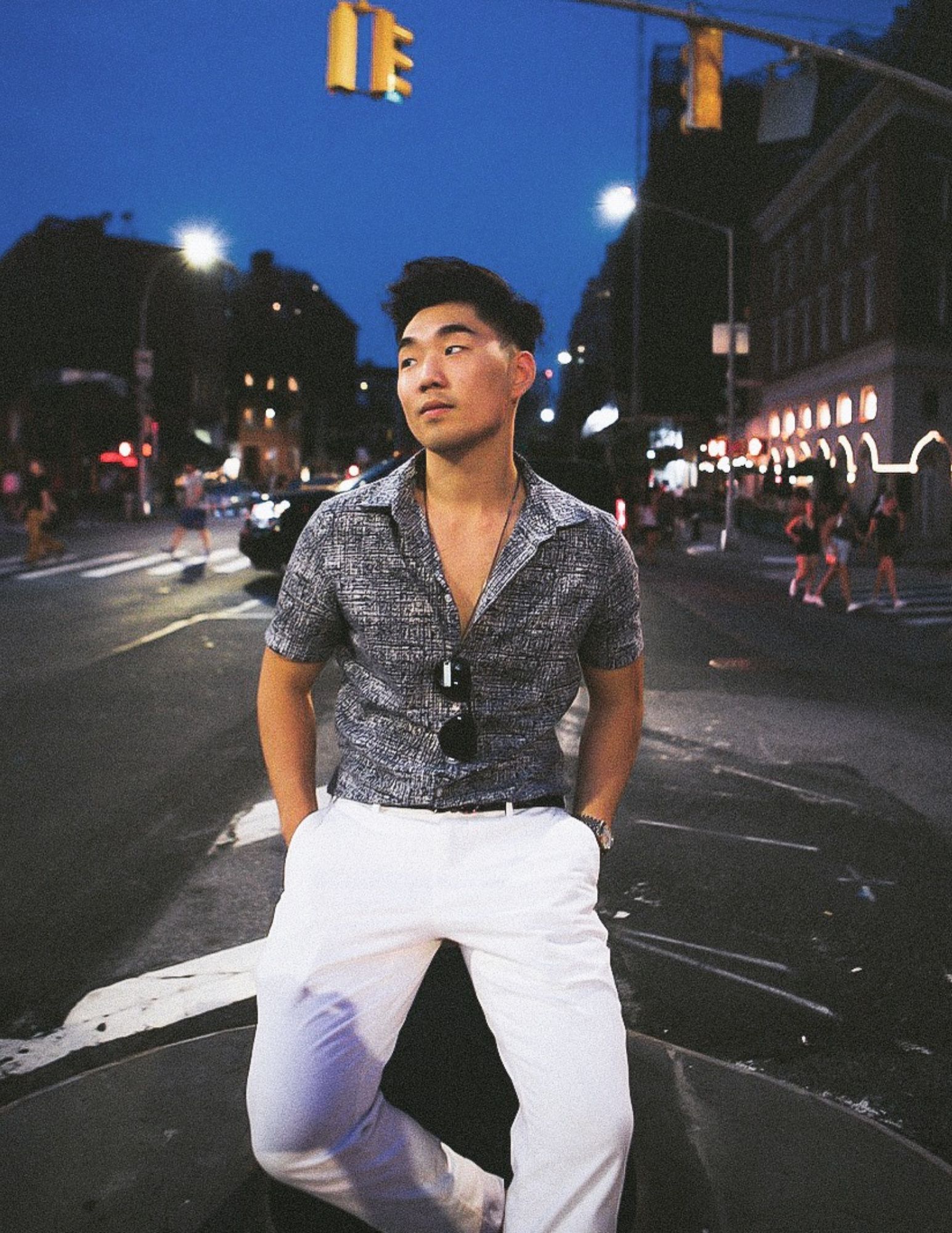

Eugene Kim, 23, New York, Ad Sales Programmer at Forbes

I feel like I struggle with my ethnic identity every day but the biggest moment of realization came to me when I first moved from Hawaii to NYC because Hawaii’s demographic is predominantly Asian. When I moved to NYC, I was put into a world where I was now categorized as a minority. On top of that, I was someone who wasn’t the best at speaking his native language either, so for a while, I felt as if I didn’t truly belong anywhere. I realized that the discovery of “self-worth” is a lifelong journey that requires constant tweaking and improvements.

As I grow older, I’ve come to realize there are certain things you can and cannot change about yourself. To promote my own identity in society, I try my best to network and support my friends who are deep within this community and to those who are making a difference. One initiative I have recently been a part of is We Power NYC. I was a part of their campaign in encouraging young voters to take action and make their voices are heard in the New York primary election. We Power NYC is a group that consists of the next generation of change-makers. Not only should we be exercising our rights to vote but these actions are what’s needed to bring positive changes to our country. Without action, thing’s stayed the same and we’re in a time where we need to be constantly improving.

In five years, I hope I’m doing some amazing things in fields I have a passion for. You’ll never know what your future is gonna be like but I do know that I don’t ever want my life to feel boring and stagnant. I want to be constantly growing, learning, and trying new experiences as those characteristics are what excites me in life. I currently work at Forbes within their ad sales and programmatic team and also am an avid martial arts fanatic who looks for every opportunity to train and enjoy the beauty of it. In 5-years maybe I’ll have a house or 7, who knows? I also hope to see more of us shown through mainstream media in a better light as I believe it is one of the catalysts that will bring all of us forward and help inspire the upcoming generations of Asian Americans to do more.

Lisa Phan, 19, Maryland, Digital Content Creator

In Kindergarten, kids would mock and say insulting terms, then stretch their eyes to make it look like my own. Realizing that I was different for the first time made me feel left out in a way as a 5-year-old. It wasn’t until I was around 14 when I started to make short videos on my iPad and watching more YouTube had I discovered Asians could be seen as “cool” too. From that point forward I was prouder than ever to be Asian American. I started using my platform to share my favorite home-cooked meals on Instagram, used my favorite songs in my videos, and proudly accepted myself.

Growing up, people around me dismissed my hard work and dedication to honor societies and my YouTube channel and used my heritage as a sole reason for some of my success due to societal stereotypes. One other case of racism is one I vividly remember from the dentist’s office. I was waiting for my younger sister to finish her appointment and these women in the waiting room were just going on and on about how we had to “go back to our country” and learn the American way. I didn’t respond because I was scared. Because racism towards Asians was so normalized, I couldn’t stand up for myself. If I did, people would say that I’m being too sensitive.

I am so proud of my vibrant Vietnamese culture and traditions and I am extremely grateful for my parents’ sacrifices as immigrants to give me life in America. Being Asian American somewhat defines the foundation of my upbringing and the morals I follow on a daily basis. Vietnamese tradition has helped me mold what I value in life and the American culture I am a part of has shaped my open mind and given me great opportunities. Asian Americans of my generation can probably attest to the fact that we hold our heritage and nationality close to our hearts and identities. Many of us grew up confused as to which society we fit in most. By blood, we are Asian, but our mindsets may match up more with the Western world.

I just want to present myself as a role model I wish I had as a little girl, or at least someone else rather than Mulan. I try my best to create in the most positive light and also share my struggles to relate to fellow Asian Americans. I want others in my community to feel supported and open to sharing their experiences. The best part of being Asian American is just having the opportunity to be part of such a diverse and inspiring community is incredible. I got to learn two languages as a baby, I enjoy a bit of the motherland at home, and then once I step outside, I’m able to take advantage of the opportunities in America.

Rosie Ainley, 22, Illinois, Filmmaker & Activist

Joining an AAPI organization at University was the absolute best move for my cultural identity. I was on the executive board of the AAPI organization there, so defining what being Asian American meant to me was something I was confronted with daily. Being able to find an actual community where people not only accepted my identity but shared the struggle within it transformed my life. It didn’t feel like my voice was falling on unwilling ears. They wanted to hear me. They understood me. They were willing to fight for my ability to just be. To me, I think being Asian American means being enriched by a distant culture most of us hardly know. But we suffer for it, and we fight for it. We carry pride in our hearts and the weight of our families’ suffering on our backs. The discipline is grounding but lifts us up to success our ancestors could only dream of.

In elementary school, I had my “lunch box” moment. I remember that it got so bad, I refused to open my lunch or even throw it away at school. I just starved myself and sat there with a closed bag while everyone else ate. I tried to hide it in the trash at home, but my parents found it and sat me down to talk about it. Maybe that’s a time I had a partial reckoning of my identity.

I’ve seen and gotten a couple of comments on social media, with the whole “Asians will eat anything” and “They should go back to their own country.” At this point in my life, I’ve gotten tired of trying to argue with those brick walls who are mostly trying to gaslight. So I let them roll off my back. When everything first started, though, and we began to see the first hate crimes and attacks in the news, I was scared. My mom was still leaving the house pretty frequently and by herself. So to imagine your mom – a middle-aged deaf Asian woman with a mask on while most people still refused one – out alone is anxiety-inducing.

When I was younger we went to family friends’ parties, where everyone spoke Tagalog and saw each other more than once a year, and all I knew was how to say “Lola” (grandma). My dad was adopted by a white family, too, so we never were that connected to our Korean side. I’ve tried learning some more words and phrases of both languages with the help of friends, but being back home again where there’s nowhere to practice is hard. It’s called “the in-between.” The struggle between wanting to know more but feeling like you’ll never know enough. The struggle between assimilating and rejecting American culture. It’s what’s made “Asian American” so hard to define.

My Asian-American identity has become a large influence on my work and will continue to be for the rest of my life. The desire to create and your culture. They’re not things you can put on a shelf. They demand your attention. I hope that Asian Americans find our balance. We’re here to stay and realize that our chance to form a strong community that can fight for ourselves and others is not something we should be taken lightly. There’s a lot of room for hope of the future. The representation in the media has already shown us a great deal of progressive change in the past couple of years. Asian America still has an incredibly long way to go, but the grassroots are growing, and we’re closer than ever to break through the bamboo ceiling.

Chloe Long, 22, Colorado, Grad Research Student

Being Asian American means I have both the opportunity and the responsibility of choosing between two conflicting cultures. I grew up in a Chinese/Vietnamese household. But my peers and my school friends are American. Being Asian American means that, for my whole life, I have been faced with two conflicting sets of expectations. I, along with many many other first-gen AAs, have had to learn for myself to choose which parts of which cultures to embody and which to set aside.

Having a foot in both worlds is great in many ways – I am exposed to different cultures and people. But there also comes the constant feeling of being the ‘other’ – never fully fitting in with a cultural group. It is frustrating. But it helps to have communities of other AAs, it makes me feel like I am really around people like me.

In undergrad, when I was Miss Vietnam for a beauty pageant I wanted to write a performative piece about unfair beauty standards that AA womxn are subject to. In doing so, I realized that my struggle with identity came from being held up to standards I could never feasibly meet from my parents and my peers. Performing that pageant piece was a turning point for me in embracing my identity. Being able to speak up about this struggle, and having people come to me after telling me how it resonated with them – that is when I really became proud of being AA and being able to speak up about these things.

The first segment of the piece talks about pressure from parents, the second segment speaks about American peer pressure. The third segment is about how the pressure from American culture along with the pressure from the Asian culture is contradictory and it’s impossible to meet both of these. No matter what, you can’t fully satisfy both. The final segment is about how, rather than feeling like you are constantly failing to meet expectations, it is our responsibility as AAs to reshape our experience by being true to ourselves. And since this was for a beauty pageant, I tied this back to the beauty and said that true beauty really is about being yourself. As I continue with that, I have written several rap-esque pieces on my experience as an AA in order to promote my identity.

I hope that we, as Asian Americans can work to establish more of a presence in media – movies, music, arts. It’s very important for America to see AA multi-dimensionality, instead of painting us as one-dimensional background characters. I’d like to see AAs portrayed as everything– we need ABGs, we need nerds, we need artsy AAs, we need gamer AAs… we need visibility for all personality types. I want the media to move away from using “Asian” as a character description, as a role in itself. We need multifaceted representation so that we can move away from America’s long history of dehumanizing Asian culture, and instead, recognize and internalize that we are American people and we are here to stay.

Dustin VuOng, 17, California, Influencer

If I could put it into just a few words, being Asian American to me is all about unity, connection, and uniqueness. As Asian Americans, we are all so different culturally and physically. Yet somehow there’s this sense of unity and connection within our community. There are always those things we could relate to each other with whether that be from our collective obsession over boba, to having strict parents or simply just not allowing shoes in the house. In the past, I’ve noticed a lot of Asians hated themselves for their race, but now people are starting to be proud of it and are identifying as being Asian American which makes me really happy.

I had to truly reckon with my identity starting middle school and high school aka the past few years and now. With me being on social media and rarely ever seeing people that look like me, it really affected my confidence and how I see myself. I used to wish I was white so bad, so I could look conventionally attractive according to eurocentric beauty standards that we’ve been brainwashed with. I am grateful to say I never really experienced too much racism growing up,I think I experienced more racism when I was older and now. Even now, I have definitely experienced some racism post-corona.

It has been a gradual transition in embracing myself and I’m still going through it. I think this past year or two is when I started discovering my self-worth. I realized how much I was just hating and putting myself down, so I started practicing self-love. I stopped with all that negativity that I was literally bringing upon myself. I was my own worst critic and hater. I started believing in my abilities and talent, my own beauty, and just myself as a human being. It’s still an on-going journey, but I’ve made some strides since then.

I practice my own Asian American advocacy and promote my identity through the content I share with my following. I talk about being Asian and my views sometimes through my videos and content. Recently for Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, I made a video called “Let’s talk about growing up Asian American” where I talked about my childhood growing up in America, my struggles, and addressed multiple controversial topics such as Asian representation in media, beauty standards, racist trends, and more

An obstacle I’ve faced is having to work way harder than any other person just because of my race and how I look. I noticed that being an Asian-American / POC that we don’t have it easy. Social media favors white people or people with eurocentric features. So not only does an Asian-American have to be “conventionally attractive”, but we also have to have talent, have a great personality, or just have that extra something “special” about us to make it in the industry.

There are so many things I hope for that I know are going to take a lot of time and work to progress. First I hope that there is no discrimination or racism towards Asians and all other POC. I hope that there is more Asian representation in the media and that it becomes normalized. Especially within the music industry because I’ve noticed there is an extreme lack of Asian American music artists. Lastly, I hope that the beauty standards change to where Asians can look at themselves in the mirror and genuinely love what they see because everyone is truly beautiful no matter what society is telling you.

Erin Kong, 22, Arizona, Interdisciplinary Artist

As a second-generation Korean in America, I have lapses in Korean language and culture due to assimilation. I was very insecure when I was younger about my Korean-ness – not to the fault of anyone, but my own self-doubt. There was so much I felt I didn’t know, and didn’t know where to start. I intentionally sought out creating relationships with other Korean people and learned how to read and write hangul. Then, I began studying Korean history. Once I did all of that, I no longer aligned myself with the identity “American.” It did not matter if America “accepted me,” because I did not want to identify with a state that committed genocide against Indigenous persons, enslaved West Africans, and decimated countries (including my own) all over the world.

I am still discovering my self-worth every day. A big part of that journey was recovering from sexual and domestic violence, and the support I received from loved ones. During my healing process, my friends were feeding me, affirming me, and loving me. Once I had the vocabulary to pinpoint reasons why things were happening, I felt empowered enough to try to love myself. I experienced many interpersonal acts of racism in life: slurs, infantilization, hypersexualization, fetishization, etc. etc. However, when examining racism and how it has operated, and continues to operate, in my life, I try to think of how it conducts itself systemically.

As a survivor of sexual violence, I think about how my body is gendered and racialized so that violence against those who look like me is normalized and enabled by the state through histories of war and violence against Asian countries (and therefore, Asian people). These wars are enabled by propaganda that dehumanizes Yellow bodies, which then, in turn, informs how I am treated in the imperial core. From a very young age, although I did not have the proper vocabulary, I was aware that these interpersonal acts of racism were flags that pointed to larger systemic issues and acts of violence against Yellow people like myself, and colonized people around the world.

There are multiple parts to my identity–gender identity, sexuality, cultural identity, etc. I’m always unpacking all the different moving parts and trying to figure out exactly how much I’ve internalized, and how to work through them. It is something that is continuously occurring. Some days I love myself more than others, but I am always putting in an intentional effort to accept myself. What really helped was finding a Korean online community, particularly made up of other LGBTQ+ diasporic folks, and feeling so less alone.

I also grew up predominantly on occupied Akimel O’odham and Hohokam land. What does it mean to be both a victim of imperialism and someone currently occupying stolen land? I think this is a question all diasporic Asians should ask themselves, and then move accordingly. For example, donating to mutual aid that assists Navajo people, who are being disproportionately affected in Arizona by COVID-19.

A question one of my friends posed to me was, “Who are you accountable to? Who are we accountable to? The people I am accountable to include Black, Indigenous, Brown, Yellow folks. I am accountable to other members of the LBGTQI+ community. I am accountable to those I love, and those I don’t know but must have a love for. I try to learn and listen as much as I can, so I can bring others’ voices in the room even if they are not physically present.

My chosen family has been incredibly supportive. Specifically, I think of all the Black, Brown, and Yellow women and nonbinary people who have loved me since Day One and hold me accountable, allowing me space to grow and change and learn and heal.

Van Sinsuan, 20, California, Student & Activist

It’s difficult for me to identify as solely an Asian American because I feel like the term is too broad to encapsulate the varying experiences that different Asian ethnic groups face. However, if I were to define what being Asian American means to me, I’d say that it means being the bridge between generations and culture, which to me is the best part.

The first time I became aware that my racial identity would be a defining factor in how I was treated as a person would be when I moved to America for the first time. I grew up in a predominantly white and Latinx neighborhood and was one out of the four Asians in my school.

Even at an early age, I experienced discrimination from my peers and was stereotyped to align with the model minority myth.

Coronavirus has only highlighted and accentuated previous experiences of racism and discrimination that I have experienced. I have experienced a much more significant amount of microaggressions and racial stereotyping than I have ever experienced before.

I constantly feel a disconnect within Asian American culture because I was raised in the Philippines for longer, but my status as an American citizen has set me apart from the people in my community in the Philippines as well. I still struggle with identifying my self-worth, but I acknowledge that I have grown tremendously from my past. The most empowered I felt was when I started transitioning and taking hormone therapy. This year has been the most comfortable I felt with my own body and skin. After experiencing a disconnect with my culture as a Filipino American during my teenage years, I also learned to fully embrace my identity and my culture when I went to college. College gave me an opportunity to experience safe spaces for other Filipino Americans as well as expand on my knowledge for my own history and identity.

I am part of many Filipino American organizations on campus that help Filipino students navigate their way into understanding more about their identity and culture. I am also part of Anakbayan, which is a Filipino youth-powered activist organization that fights for human rights and the national democratic movement. In my personal life, the love that my family and closest friends have given me is what has pushed me to be the person that I could be today. In five years, I hope to find myself finished with film schools and starting my own work as a filmmaker.

As Gen Z, I have seen that we have more resources and knowledge of decolonizing our minds and that we are more accepting of change than our previous generations. I want Asian America to be able to self criticize and reflect on racism, especially anti-blackness, within our own community and find ways to decolonize internalized racism. We still have more work to do, but I am proud of the progress we’ve made in reconnecting with our roots and our culture.

Pranjal Jain, 18, New York, Activist & Founder of Global Girlhood

I came to America when I was 6-months old and was undocumented for the first seven years of my life. I didn’t have a passport, yet I still had a lot of Indian culture in my life. When I did go back to India I was able to see amazing cultural aspects, whether it be our food or how our culture goes back so many years and it’s remained unchanged and authentic to what it was in the beginning. I think that because of that background in this hyphenated identity being Asian American has really changed for me and it continually changes especially as I grow in age.

Global Girlhood is an organization that is revolutionizing representation by leveraging social media to share everyday women’s stories of empowerment from all over the world. I think it’s so rooted in my own story as a former undocumented immigrant because growing up, I would never see women that were doing the work that I wanted to do in my life or even represented in media. That is why I do what I do at Global Girlhood and I’m also the Associate Director of Gen Z Girl Gang, an organization that is redefining sisterhood for our generation. We’re invested in creating communities of women that are up to date with each other, invest in each other’s success, and understand the power that we collectively hold when we are collaborating and not competing.

I practice my Asian American advocacy by first, starting at home. WhenI was younger I’d get a lot of “You need to look how to cook or else you won’t get married,” and they would tie my worth with how “marriageable” I was. Over the years I worked to distimitaize this by saying things like, “Oh, I don’t need to learn how to cook because I’m going to be working and I’m going to be so successful that I’m going to hire someone to cook for me,” in joking coequal ideas that they would understand too. But I have seen myself truly breakdown these misogynistic ideas that my parents and their parents held and I’ve seen myself make space for myself. It’s hard and it takes a lot of time but I think that if you can do it to your family, not only do you change your own life and the lives of the people in your community, I think you gain a lot of courage. Standing up to your family truly seeing that change manifest gives you that power and experience needed to do that in the real world.

I walk into rooms with so much more depth and understanding of how the world works on the other half because I am Asian American. I understand what growing countries may look like. I also understand the importance of ideas and traditions and why tradition untouched is so revered and has so much sanctity to it and balancing ideas. Being fluent in Hindi and being able to read and write it also exposed me to a whole different set of ideas that had given me the opportunity to consume things with an Eastern lens because so much of Western media, and books are influenced by colonized ideas

My favorite and most rewarding thing about being a leader in space is getting the chance to cultivate other leaders’. Global Girlhood is like my love letter to the world, truly combining all the best things in my life at this point in efforts to pass it on to other young girls and women. So many times when you scroll through social media there are ideas about what set empowerment looks like, what power looks like, what success looks like, etc. and Global Girlhood tries to break down those barriers so that someone all the way in Japan would be connected with someone in California. The more we can do that I believe, the more we create a justice society, because I think stories have the power to expand our capacity for understanding and revolutionize the way we tackle problems and ideas.

I have been limiting my consumption of media to only WOC authors or things that are written about POC. I really see myself reflected in those pieces and just in general with other Asian identities. ‘Crazy Rich Asians’ for example, having such a beautifully made movie and something that is so consumed by mainstream culture I think automatically adds to us. A really good way to see more of these identities is to limit our consumption because people are only going to make what other people are watching. The more things that you watch that are written in diversity the more initiative producers have to make things like that.